The statue of Sir Redvers Buller, a Victorian army commander, in Exeter has recently received a new interpretation board contextualising his career across the British Empire. I played a largely informal role in the project led by Prof Nicola Thomas, which led to that board. In this blog, I tell the story of Buller’s career, fleshing out the content of the new board.

Statue of Redvers Buller, Exeter from the website of Historic England

Buller and the Boer War

Redvers Buller is best known for commanding British forces during the South African (Second Boer) War. After losing three successive battles attempting to relieve the siege of Ladysmith, his critics nicknamed him ‘Reverse Buller’. He was a popular member of the local gentry in Exeter though. The statue of him was erected by subscribers demonstrating their support in 1905, after he was dismissed from any command for publicly defending himself from press criticism. His supporters wished to preserve a public image of Buller as the man who had at least successfully defended the colony of Natal from a threatened Boer invasion, rather than someone who had lost hundreds of British troops in ignominy. Hence the statue’s inscription ‘He Saved Natal’.

The South African War came at the very end of Buller’s career, however, and it was essentially a contest between two different visions of white supremacy. Buller was part of the blunt force required to reshape the region as a confederation of British – administered territories financed by the gold mines of the Rand around Johannesburg. British mine owners and officials envisaged a modern, urbanised and industrialised South Africa, exploiting cheap and controlled African migrant labour recruited from ever-diminishing reserve lands. The Boer governments of the Orange Free State and Transvaal, however, were fighting to preserve an independent, more agrarian version of white supremacy.

Although Buller has been associated with the policies of concentration camp internment, confinement through barbed wire fences strung between block houses and mobile infantry sweeps, which finally induced the Boers to surrender in 1902, he had in fact left South Africa after finally reaching Ladysmith. This was before the Boers resorted to the guerrilla tactics that ‘necessitated’ these measures.

Given that Buller was fighting white colonists whom he frequently claimed to respect in the Boer War, and that he was not responsible for concentration camps, it is surprising that some of the activism around the statue inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement focused initially on this episode in his career. All the more surprising when we examine Buller’s prior career. Stretched across the breadth of the British Empire, that career was based on conquering and dispossessing people of colour, whom he and his peers generally dismissed as “savages”.

India and China: rebellion, looting and racial stereotypes

Buller joined the British army as a young ensign in India in 1858 as the suppression of the Indian Uprising of the preceding year was reaching its final stages. Flying columns of British troops were rounding up and summarily executing the remaining rebels. The rebellion had

markedly affected popular British views of Indians as a race, especially after the mutineers’ killing of British women and children at Cawnpore. In October 1857 Charles Dickens wrote “I wish I were the Commander in Chief in India …. I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested … proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth.” Introduced into the Army in this atmosphere of racial hatred, as captured mutineers were being blown apart from the mouths of canons, Buller was sent to China in February 1860 during another campaign of racial vilification.

In 1857, Prime Minister Palmerston had forced the Second Opium War on the Qing Dynasty. Canton was one of five ports that the British had forced the Chinese to open for the opium trade from British India during the First Opium War. By the time Buller enlisted, there was growing pressure to further prize open China’s vast but protected market on behalf of British manufacturers, and to push for further concessions for the opium trade, including its legalization. Palmerston had seized upon the Chinese authorities’ impoundment of a ship formerly registered as British to provoke war. Calling a general election, he solicited the cartoonist George Cruikshank to circulate images of Qing methods of torture and execution and lied that British heads had been displayed on the walls of Canton.

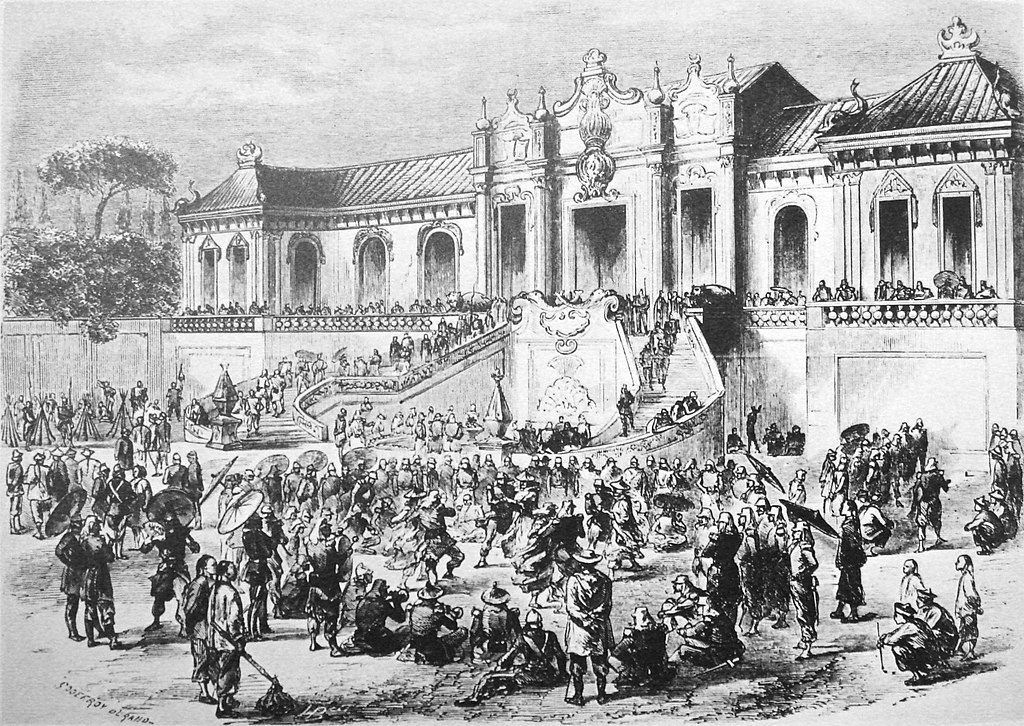

Having imbibed the post-rebellion atmosphere of racial hatred in India, Buller was sent straight to China to join the occupying army. He was not particularly enamoured of the causes of the war and he saw little fighting there, but was present when the Qing summer palace was looted, acquiring “splendid shawls, chess men and fine old enamel ornaments from the Empress’s dressing table” for his sisters. Buller had left for home before the palace was finally burned down, but Charles George Gordon, whom Buller would later try to rescue from Khartoum, complained that “These palaces were so large & we were so pressed for time that we could not plunder carefully”.

Buller’s statue presents an opportunity to reflect on the racial stereotypes propagated in Britain during his youth, about both Indian and Chinese people, and about the trade in narcotics, which underpinned British commercial dominance in the East. The repatriation of plundered artefacts is something that I will return to below.

The Political Context: Confederation

The policy which did most to shape Buller’s impact around the world after his early Indian and Chinese experiences was that of Confederation. It was pursued by Lord Carnarvon,

Secretary of State for the Colonies under Prime Minister Disraeli. The shock of the Indian Uprising and the need to coordinate the response between separate governmental offices, had prompted more integrated imperial governance from a new building (the current Foreign Office) in King Charles Street, London. There, the new India Office, which took over from the East India Company, the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office occupied connected wings.

The policy pursued by the officials in King Charles Street followed closely an agenda outlined by Charles Dilke’s popular book Greater Britain, published in 1868. Dilke’s rumination on the scope, nature and purpose of the British Empire captured perfectly mid-Victorian Britons’ sense of themselves as a people of unrivalled achievement, moral ascendency, global leadership and racial superiority. For Dilke, “The idea which in all the length of my travels has been at once my fellow and my guide … is a conception, however imperfect, of the grandeur of our race, already girding the earth, which it is destined, perhaps, eventually to overspread”. The “defeat of the cheaper by the dearer peoples” was an essential precondition for the spread of civilization. Carnarvon’s major preoccupation in his first term as Colonial Secretary in the mid-1860s was the confederation of the separate Canadian colonies of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick so that they could form a better administered and more prosperous whole within this Greater Britain. Buller was employed in pursuit of this vision of imperial consolidation.

The Red River Expedition: Learning the Trade

Buller first came to the attention of senior officers as a capable solider in the Red River Expedition of 1870. In 1869 Métis people – Catholics of mixed First Nations and largely French colonist descent, recognised as aboriginal to Canada – led by Louis Riel, had established an independent government of their own at the Red River Colony, in today’s Manitoba. They did so rather than be absorbed into the new Canadian federation as Carnarvon wished.

The recently unified Canadian government had purchased the territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company and appointed a governor to allocate the land to British settlers and integrate it with the rest of the federation regardless of the Métis inhabitants’ wishes.

Having turned back the British surveyors and occupied Fort Garry, Riel and his followers declared their intention of joining the federation, but on their own terms. They sought to negotiate representation in Parliament, a bilingual legislature and chief justice, and recognition of existing Métis land claims. They elected an assembly of twelve representatives from Anglophone parishes and twelve from Francophone parishes, but after the execution of an Orangeman who sought to overthrow them, Riel and his provisional government were deemed to be in rebellion.

Although the expedition launched by General Wolseley and including Buller arrived at Fort Garry too late to capture Riel and his followers (Riel watched from the far bank of the river as Buller entered the abandoned fort), Buller had successfully led his men across some 550 miles of largely water-borne travel, carrying boats across the strips of land between the heads of lakes and rivers. In suppressing the most viable attempt by aboriginal people to have their interests represented in Canada, he earned his reputation as a promising young officer with a real grasp of logistics, supplies and planning.

The Asante Expedition and Colonial Plunder

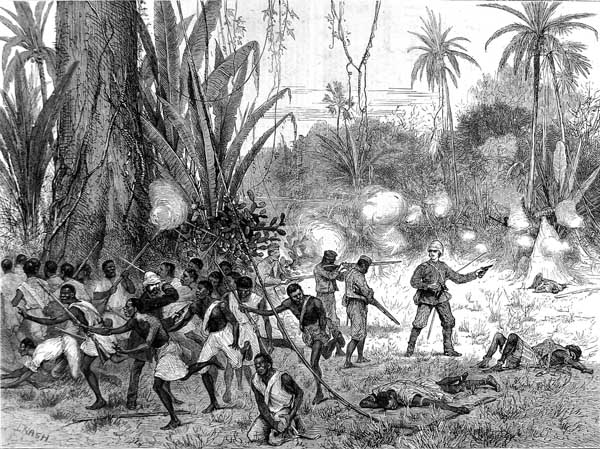

Through the connections forged with Wolseley on the Red River expedition, Buller was ordered to join the famous general’s next punitive colonial expedition, against the Asante kingdom of West Africa. He was appointed head of intelligence and given the chance of scouting the advance on the Asante capital Kumasi.

In 1872, the Colonial Office had sought to consolidate Britain’s fragmentary governmental entities on the West African coast – a policy in accord with the larger objective of confederation in the settler colonies. This included the purchase of the Dutch Gold Coast with its port of Elmina, and its incorporation within the British Gold Coast colony. However, Elmina was also the powerful Asante kingdom’s sole remaining trade outlet on the coast, and a key source of its revenue. In early 1873 Kofi Karikari, the Asante king, ordered his army to attack the British at Elmina in an attempt to reclaim the port.

Wolseley led a British expedition including Black West Indian troops and Fante allies to destroy Kumasi. Scouting the route ahead, Buller and his men burned down villages to deny Asante forces food. The expedition was justified in Britain as an attempt to end Asante practices of slavery but used enslaved women among the 17,000 porters employed to carry its own equipment. After his surrender in 1874, Kofi Karikari was made to pay 50,000 ounces of gold, “1,000 ounces … forthwith, and the remainder by such instalments as her Majesty’s Government may from time to time demand”. He would also keep the inland trade routes open, and halt both human sacrifice and slavery. Policing the treaty meant that the Colonial Office was ineluctably drawn into responsibility for an ill-defined British ‘protectorate’ stretching well inland from the Gold Coast.

Buller not only scouted the route to Kumasi but was appointed the Prize Agent for the plunder of the Asante capital after its capture. This role, outlined in his commanding officer’s Soldier’s Pocket Book for Field Service, involved advising on whether plundered items should be auctioned among soldiers on the spot or sent home to be auctioned on behalf of the participating troops. After the agent’s fees had been deducted, the remainder of the funds raised were allocated to the soldiers in shares depending upon their rank, with generals earning four hundred times the amount of privates. Buller sought to collect the plunder to auction it at the Cape Coast, but was unable to prevent both soldiers and British newspaper reporters smuggling out their own private booty. The official haul included King Kofi’s state umbrella and a golden stool, which Wolseley gave to Queen Victoria, and which are still in the royal collection.

Buller’s prize auction proved disappointing and most of the gold items were carried back to Britain for auction or display. Garrard & Co., the official crown jewellers, bought several gold items for £11,000 and sold them on again in the spring of 1874. Since the prize money was considered too little to distribute among all the soldiers who participated, Disraeli’s cabinet decided to award them an extra thirty days pay in lieu of the prize money they would have expected. Much of the plundered Asante gold is now in the British Museum; the Wallace Collection; the Royal Artillery mess at Woolwich; the National Army Museum and the Green Jackets Regimental Museum. As the Ghanaian journalist Kwame Okopu has noted, in 1974, on the centenary of the plunder and burning of Kumasi, “Memorial services were held [in Ghana] and people sang funeral dirges and wept. At a ceremony attended by millions in Kumasi, the then Asantehene, Otumfuo Nana Opoku Ware II … declared it was time the British returned the regalia and appealed to the British to return the sacred objects”. Since then, Ghanaian representations have been relayed between the British government and museums with no further progress towards repatriation aside from the return of some items held in private collections.

Buller’s statue potentially presents a focal point for educational and restorative projects exploring the ethics and practicalities of repatriating these stolen objects.

The Wars of South African Confederation

Having helped bring the Asante kingdom under British ‘protection’, Buller next joined the long running campaign to bring Southern Africa’s diverse colonies and independent African kingdoms under confederated British rule, following the Canadian precedent.

Carnarvon had sent Sir Henry Bartle Frere to the region as High Commissioner, determined to bring about a unitary British government. The project began with the fortuitous absorption of the Boer-governed Transvaal in 1877. Frere’s next step was the conquest of the remaining independent African polities interspersed between the Boer Orange Free State and British-run colonies of the Cape and Natal. The mixed descent Griqua, the Gcaleka Xhosa, the Zulu and the Pedi were particular targets.

In 1878 Frere launched his war against the Gcaleka Xhosa. These people were the branch of the amaXhosa who had held onto their territory across the Kei River from the Cape Colony through eight previous frontier wars and despite the absorption of their kin, the Rharabe Xhosa, to the west. As the Gcaleka fought desperately to avoid the fate of the Rharabe, the Rharabe chief Sandile rose in rebellion within the colony. Buller’s task was to flush him and his followers out of the mountainous, densely vegetated, Pirie Bush.

Buller led his colonial troops in a scrambling slide down a precipitous slope to attack some of Sandile’s followers, killing fifteen of them as they sought to hide in a cave. Although he was not part of the detachment of Mfengu African allies that hunted down and killed Sandile himself, there may be an opportunity to link Buller’s statue with the memorial to Sandile, erected in 1972 at his grave near King William’s Town, and to reflect on what this final conquest and absorption of the Xhosa people meant for South Africa’s African population.

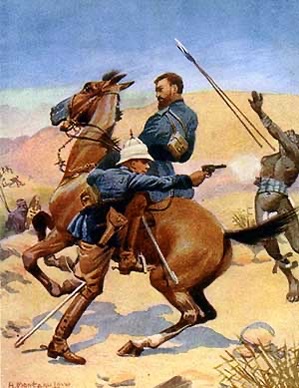

Buller returned to South Africa very shortly after the Ninth Xhosa War to engage in Frere’s next war of confederation, against the Zulu, launched with an invasion of Zululand in January 1879. Buller earned his Victoria Cross by rescuing three men from the oncoming Zulu army as he and his mounted colonial troops withdrew from the hill at Hlobane.

The following day, at the Battle of Kambula, Buller led a mounted infantry charge to kill as many Zulu as possible when they broke off the attack and ran from the concentrated British fire. A Captain D’Arcy wrote that Buller and his men “butchered the brutes all over the place,” while Buller himself was, “like a tiger drunk with blood”. Following the charge, the British infantry and African auxiliaries combed the field killing any wounded or hiding Zulus – as Zulus had done to British wounded after the Battle of Isandhlwana. Around 750 Zulu men were killed in the initial attack at Kambula, but Buller’s charge and its aftermath killed another 1,200. At the final battle of the war, when the British turned Gatling guns on the charging Zulu at Ulundi, Buller led another mounted infantry pursuit, killing up to 2,000 more Zulu men as they fled.

Not only were tens of thousands of African people killed in Carnarvon, Frere and Buller’s wars of South African confederation, but viable, independent societies were broken apart and families separated as the template for apartheid was laid. After the fragmentation of their kingdoms, Xhosa and Zulu men were obliged to engage in migrant labour, working at low wages for white employers in South Africa’s towns and cities, their mobility policed by pass laws, while women were left to scrape a subsistence for themselves and children in environmentally degraded reserves. During the ensuing decades and especially after the South African War, this system was refined by the British investors in South Africa’s industrialisation and British governments. It was inherited and turned to specifically Afrikaner purposes in the guise of apartheid after the 1948 election of the National Party.

Egypt and Orabi Pasha

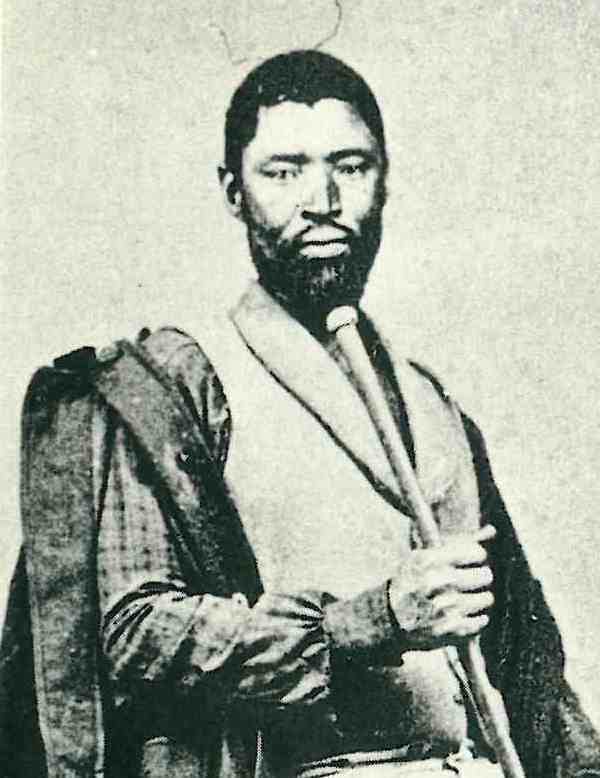

Having helped subjugate Black South Africans in pursuit of confederation (a policy put on hold after Carnarvon resigned in 1879 and then Gladstone took over from Disraeli as Prime Minister), Buller’s next war was waged to preserve control of the Empire’s main strategic lifeline. Egypt was nominally an Ottoman territory but governed by a pasha who had become indebted to British and French financiers and governments. Its Suez Canal played a vital role connecting Britain with India and the colonies of the southern hemisphere, so when Orabi Pasha, a soldier in the Pasha’s army, led a rebellion against indirect Anglo-French control in 1882, the British government intervened.

One of Orabi’s demands was for an Egyptian parliament like the ones that liberal Britons demanded for themselves, but which they consistently denied colonised people of colour. His

was a proto-nationalist rebellion which predated that of Nasser, who nationalised the Suez Canal some seventy years later.

After British ships had shelled Alexandria, Buller reconnoitred and led British troops in the suppression of Orabi’s revolt at the Battle of Tel el Kebir. Some 2,000 Egyptians were killed in the encounter.

Orabi Pasha was sent into exile in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where he set up the first Muslim school. A cultural centre named after him and run by the Egyptian embassy still exists in Kandy, to foster understanding between Sri Lanka’s religions. A potential link between the statue in Exeter and the centre in Sri Lanka might be one way of highlighting the unexpected connections between places and peoples generated by the British Empire and its servants.

Sudan and the Mahdi

The following year, 1883, Buller was back in Egypt again, this time fighting the revolt led by the ‘Mahdi’, a religious leader of Sudanese groups resisting control by the British-baked Egyptians and objecting to the Ottomans’ lax version of Islam. General Gordon had been sent to Khartoum to oversee the withdrawal of Egyptian troops but had chosen to remain there, possibly to elicit British intervention despite Gladstone’s government’s reluctance.

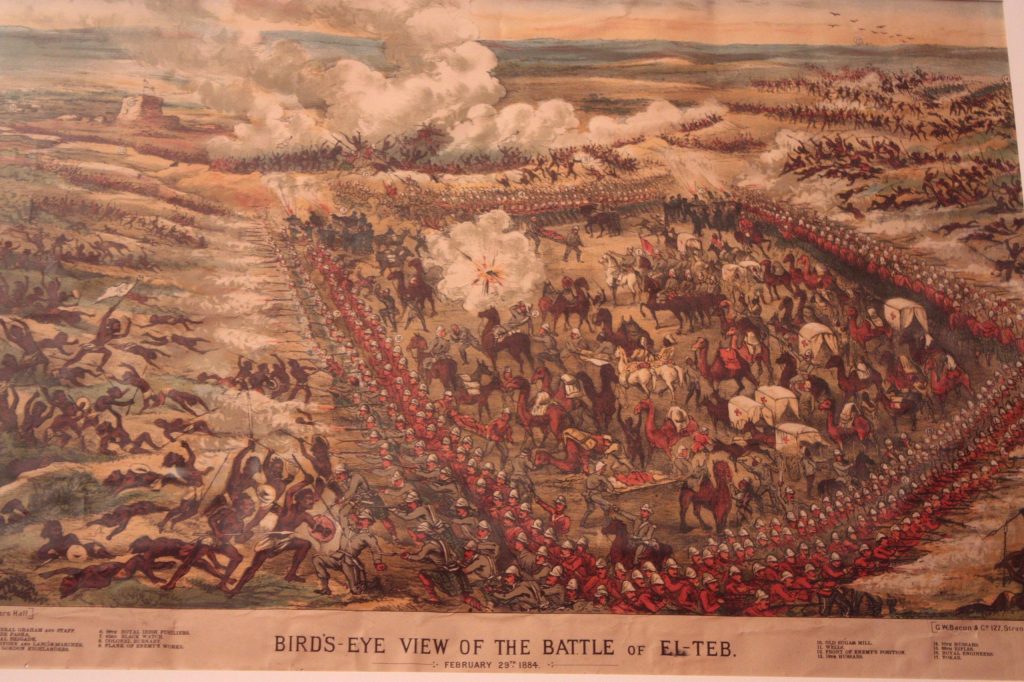

Buller fought at the second Battle of El Teb, in which 2,000 of the Mahdi’s followers were killed, as part of a relief army sent to save Gordon. After the battle Buller’s bravery was noted as he sat on his horse issuing orders while bullets ‘bespattered the rocks all around’. The orders he was giving at the time were to burn a village to the ground. He then deployed overwhelming firepower to kill 2,500 more of those whom the British called “Fuzzy Wuzzies’’ at the Battle of Tamai.

Buller took command of the relief column once it had reached Khartoum only to find Gordon already dead, and oversaw its withdrawal. He would be criticised by some after this campaign for having filled in desert wells so as to deny the Mahdi’s army (and anyone else) access to water.

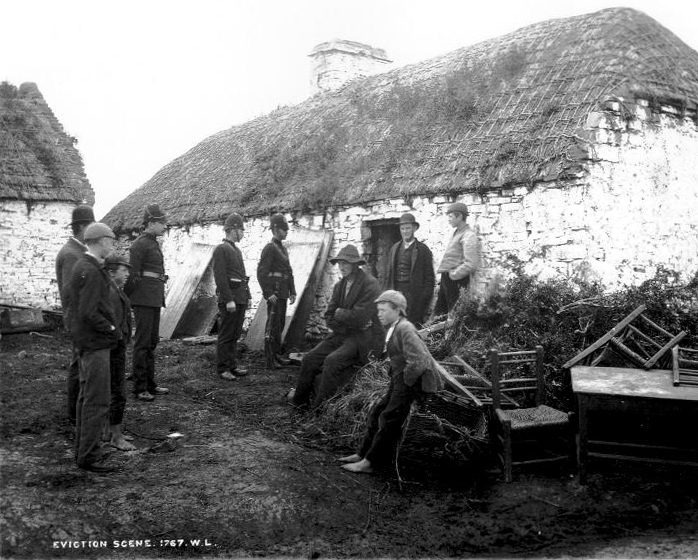

Intelligence in Ireland

In 1886, Buller’s record of intelligence work prepared him for the job of putting down the long-running ‘land war’ in southwest Ireland. Since 1879, ‘Moonlighting’ gangs had been attacking landlords and rent collectors and organising rent boycotts against landlords who refused to lower rents, despite widespread poverty and high food prices during the ‘long depression’. Buller’s instructions, issued in the immediate aftermath of the defeat of Gladstone and Parnell’s Home Rule Bill and the election of a new Tory government, were to reorganise the Royal Irish Constabulary to suppress the insurgency.

The appointment of this now celebrated soldier to a police role was portrayed initially by Irish nationalists as a desperate and oppressive resort by the British government, who were now treating the Irish like the “savages” whom Buller was used to fighting. However, during the two months he served in the role, Buller actually criticised the exploitation of the Irish peasantry by rapacious absentee landlords, who failed to uphold his own paternalistic ideal of the gentry. “The real evil in this country”, he wrote, “is want of money”. At the same time, he mobilised a network of paid informers to arrest the leading ‘Moonlighters’. In Clare and Kerry he developed the most sophisticated spying network of the British Empire outside of India.

Serving briefly as Permanent Under-Secretary for Ireland immediately after his police role, Buller continued to argue that curbing the excesses of the gentry was as much part of the solution to Irish governance as more effective policing. As a contemporary newspaper pointed out, “his sympathy for the Irish peasant was similar to his attitude towards the Boers”, both of course White subjects of British imperialism.

Buller’s final roles before heading off to fight those Boers were as Quartermaster General and then Adjutant General at Army Headquarters, which gave him the opportunity over ten years to reorganise the institution. He did so based largely on his experience in the Red River, Asante and Egyptian campaigns, his major contribution being the creation of a new Army Service Corps to bring about greater efficiencies in supply and transport to troops on campaign. Although his emphasis on mobile and self-reliant troops went some way towards preparing the army for the Boer War, when he got to South Africa he would find that it was not far enough.

Conclusion: Black Lives Matter?

Throughout his career, Buller was respected and even adored by British troops under his command, for the care that he took to protect their lives in battle and his determination to share their hardships. He was a brave and capable soldier and an excellent logistician. He had a good reputation as a landowner and supportive member of the community in and around Exeter.

However, he had repeatedly been cast into environments around the world of which he had very little understanding, with orders to kill and subdue people of colour.

In the battles in which Buller personally fought, at Kambula, Ulundi, Tel el Kebir, El Teb and Tamai, around 10,500 people of colour were killed. We do not know how many Chinese, Asante and Xhosa were killed by the troops under his command because no count was conducted. Buller could display compassion, for instance to Zulu women and children who were allied with the British in the Anglo-Zulu war, carrying some of them away from the advancing enemy on his horse and expressing his concern for them. However, his respect for the Empire’s white subjects, both Boer and Irish, and his regret of the need to fight them was more consistently apparent.

Like his contemporaries, it is indisputable that Buller behaved as if Black lives mattered little compared to white lives. The main purpose of his career was the subjugation of independent Black societies to serve British interests, albeit sometimes justified by antislavery intentions and compassion for the victims of Indigenous rulers.

Like others in the British army Buller consistently employed scorched earth tactics to achieve victory. He destroyed villages in the Asante campaign, the Ninth Xhosa war, the Zulu War and in Egypt, regardless of whether their inhabitants were combatants or not, and filled in desert wells in Sudan, to deny local people access to food and water. Such tactics would only become controversial in Britain when they were deployed against the Boers. According to the military historian Edward Spiers, the looting of enemy settlements, in which Buller had played a significant role, would also become “an embarrassment … only after the extensive pillaging of European [Boer] property in South Africa”. Thereafter, Wolseley’s advice on how British soldiers should allocate loot was replaced by Kitchener’s injunction that soldiers should “always look upon looting as a disgraceful act”.

The reputational damage that Buller suffered in the Boer War, and which led to the erection of his statue, can also be seen as a result of his prior experience killing only people of colour. As Miller Maguire put it in the Morning Post, Buller and his cohort “were so accustomed to cheap victories over badly armed [indigenous peoples] … that they could not comprehend the difficulties … in … warfare” with a force equipped with similar weapons. Buller was defeated for the first time in the Boer War because neither he nor his counterparts “had taken the pains to study … the probable effects of magazines and smokeless powder”, which the Boers were able to obtain through trade with Germany.

The argument that Buller was a man of his times rings true, even though he was directly responsible for many more deaths than most of his contemporaries. However, it is precisely a clear-eyed awareness of what those times were and how we might wish to commemorate them that is needed today. What lessons can Buller’s statue teach Britons about the nature of an empire that is still naively mythologised as benevolent by many? Perhaps we might use Buller’s statue, in situ, and according to the government’s Retain and Explain policy, as a focal point for new connections with the peoples and places he helped to conquer. We might employ it to educate Britons, who are used to the disavowal of harm to distant peoples, about the effects of the British Empire on people of colour.

Sources

Primary

National Archives

Buller, Sir Redvers Henry ((1839-1908), Knight, General

Crediton

Documents relating directly to the Buller Family (a finding aid related to materials held at the Crediton Area History and Museum Society)

Secondary

Lewis Butler, Sir Redvers Buller (Classic Reprint), Forgotten Books, 2018

Norman F. Dixon, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, Basic Books, 2016

Walter Jerrold, Sir Redvers H. Buller: The Story Of His Life And Campaigns, Kessinger Publishing, 2009

Alan Lester, Kate Boehme and Peter Mitchell, Ruling the World: Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2021

Charles Henderson Melville, Life of General the Right Hon. Sir Redvers Buller, BiblioLife, 2009

Geoffrey Powell, Buller: The Scapegoat? – A History of General Sir Redvers Buller, V.C., Leo Cooper 1994