This week, I finally found the opportunity to take myself to Shrewsbury to undertake research on the history of the statue of Robert Clive situated in this historic market town in county Shropshire, near the border with Wales. The trip opened up as many questions as it answered.

Shrewsbury is a beautiful town, enclosed in a meander loop of the River Severn. The station building itself is gorgeous, with little decorative stars lined up on the top of the stone front – there must be a technical name for this, but I have no idea. The historic centre, a mere ten minutes walk from the station, boasts narrow cobbled streets with seriously odd names (Grope Street, for one), and many well preserved Tudor shop and house fronts, now also bearing signs for the best high street brands. The Shropshire Library and Archives is in a gorgeous old building too, just a minute’s walk from the station.

The archive is an absolute joy to work in. For a South Asianist, whose idea of local archives involves industrial amounts of dust, insect-droppings, dark rooms, rickety chairs and impossible facilities, this was as good as a spa holiday. Beautiful, large, well-lit rooms, lots of tables, easy rules for photographing and the kindest archivists one could hope for. Waiting for me already were files of documents related to both statues – the one installed in Shrewsbury in 1860 and the one unveiled in London in 1907.

I began with the 1907 set. I had already looked at materials related to this statue in London. The private papers of Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India 1899-1905, contained a sub-series of mainly personal letters in which various Shropshire individuals, old India hands and a smattering of eccentrics urged him to organise a demand for a suitable memorial for Lord Clive. It was an easy sell for Curzon, a heritage and empire enthusiast in equal measure. To make a point to pesky Indian nationalists, he had already undertaken to create memorials in the battlefield of Plassey, where in 1757, Clive’s intrigues had led to the ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-daulah being cheated by his own relative and military commander in a confrontation with the East India Company. It was hardly a battle; the outcome had been decided by intrigue. Enthusiasts for the memorial did not see ‘Plassey’ and its hero in this way, however. They saw in Clive a repository of masculine virtues that made him a suitable model of civic virtue for an imperial nation. They did not explain how conspiring with foreign princes, extracting huge kick backs and creating misgovernment that led to the death of millions of humans added up to civic virtue. There was silence on these matters, as if none of that happened.

It was very similar in the complementary letters that I saw in the Shropshire archives. What these opened up further was the tangling of aristocracy and empire, such that Clive’s descendant, the then Lord Powis, expressed enthusiasm but noted that it would ‘not do’ for him to be the main organiser for the memorial. A great deal of activity was led by Lord Wakeman, the fourth in line of the Wakeman baronetcy, created in 1828 (I saw the impressive deed).

The journey from Exeter to Shrewsbury had been tortuous and long due to storms leading to train cancellations and so on (the joys of British November), and the archive shut at 4 pm before I could do much more. I ambled over to the library portion, taking in the statue of Darwin in front of it, sat in a benevolent scholarly pose, and wondered for a moment whether and in what ways this statue was colonial too. Night was falling fast, and I was determined to meet Clive on the first day, so I walked to the main square. And there he was, stood on a pedestal with only ‘Clive’ written on it (and hardly visible in the dark). It was definitely underwhelming. I sent a photograph to a friend, and she said ‘It looks like he is waiting in a queue.’

There was an interpretation board next to the statue. I had read in newspaper articles online that this board was the result of almost three years worth of discussion, debate and ultimately, project management by the Shropshire Museums Service, who drafted the wording on the board. It said that Clive was a ‘controversial figure’ and then proceeded to note the ‘atrocities’ he inflicted on Indians. I noted idly that nobody says Hitler was a controversial figure; Clive clearly did not make the cut-off from controversial to monstrous.

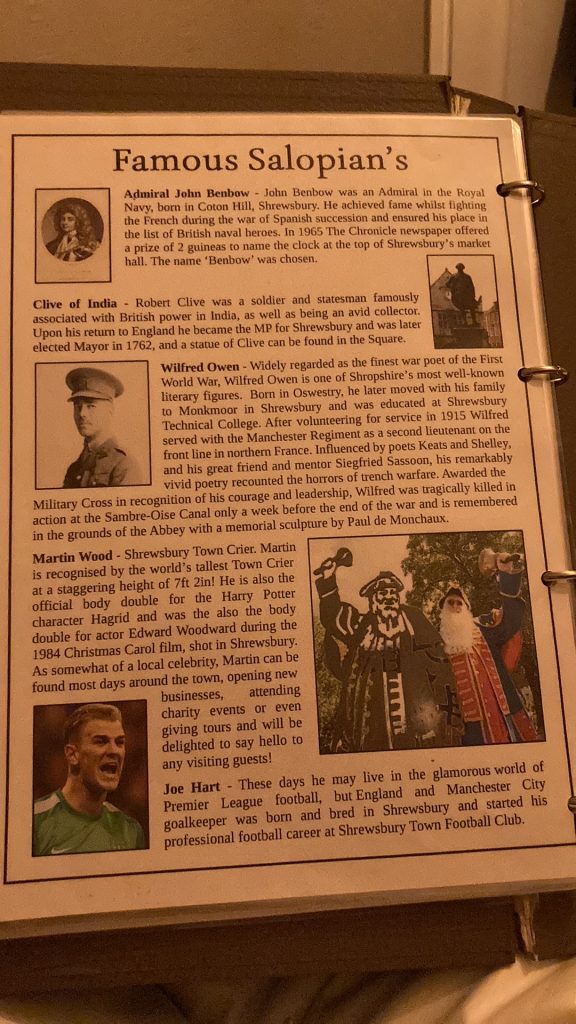

My sense of gloom deepened as I reached my very pleasant hotel room and opened the information file. This included a page of guidance for tourists, titled Famous Salopian’s (yes, arrgh misplaced possessive), and it mentioned Clive. It said that he was ‘soldier and statesman famously associated with British power in India, as well as being an avid collector.’ An avid collector? Is that a reference to the Clive collection at Powis castle, one of the largest collection of Mughal artefacts outside India?

But the morning dawned bright and sunny. After a most pleasant breakfast, I stepped out into the square again. It was transformed! There was a bustling farmers’ market, which stalls of food, sausages, cheese, chocolates, ceramics, scented candles, trinkets of all sorts. There was somebody playing music and everybody was smiling. I smiled too, at the lady selling African goat curry and rice in one of the stalls, and the young women and men in uniform raising money for Royal British Legions poppy appeal. I went in to see the Shrewsbury museum and art gallery and found a really enjoyable space, with lots of interpretation of the pre-Roman Bronze age, Roman, post-Roman, Norman, medieval, Tudor and Stuart artefacts in their collection. An immersive installation explained how Bronze age roundhouses were inhabited; children were invited to make mosaic patterns following or disregarding the Roman models; portraits of local law officials and merchants together with their pleasant-looking wives smiled at me; a beautiful community project of recreating a typically tiny Tudor bed with elaborate hangings really warmed my amateur craftswoman’s heart.

There was no Clive, however. Nor were there any images, implements, ideas, anything of the millions of Bengali people who died because of his actions. I stepped out again, went and did a stint at the archives and returned for lunch. Slurping goat curry, I looked at the happy crowd and observed. Nobody looks at the statue. It is just there. Is that a metaphor for empire in Britain?