Archives are about power. Documents, issued by the right authorities and stored in the right places establish truths – about people, events, countries, communities. Being ‘undocumented’ thus implies a dangerous and criminal invisibility – an undocumented person is assumed to be in breach of the law, undeserving of legal protections, even human sympathy: a body out of place.

Since at least the 1980s, historians, art historians, anthropologists and linguists (among others) have been thinking about the archives a bit more sceptically. Many now acknowledge a broad archival turn, which means that we are more aware than before that archives are not just neutral sources of facts. They are actually created by people in power to tell certain stories, and in many cases, those stories become so powerful that most people can only think in those terms, including those who are depicted unfairly and inaccurately in them. While this has made many scholars feel that archives are tools of oppression, others have noted efforts to harness the power of documentation, in order to tell other stories, to claim space.

In our project on disputed memories and memorials of colonial/imperial pasts, archives are tools of collective memory. A leading scholar on this subject is Aleida Assman, who proposed that beyond direct person to person transmission of memory, which can only work across a few generations, society needs specific tools to hold and transmit collective memory; archives are among such tools. How then, do we locate archives in our study of memory centred around public statuary?

One simple and obvious approach is archival research – to find out who a certain statue depicts, what their life’s events were, who proposed and paid for a public memorial for them, which artists were involved, what alternative designs were proposed, and what others said or did in relation to or around that statues subsequently. This, indeed, is the approach taken in most art historical studies of statuary, including the multi-volume Public Monuments and Statues of England (Liverpool University Press, date range). All of this is important to us too, but this privileges research in a particular kind of archives – that of the art association, the city history museum, the local council, and so on. In such archives, people who do not share such memory are visible only when they dissent, loudly and violently.

On 13 and 14 June, we were fortunate to be able to host a number of experts for an intense two-day workshop on radical archiving practices. For this, Cast in Stone joined hands with the project South Africa’s Hidden War, and was supported by the University of Exeter’s Global Partnerships with a grant. This grant enabled us to host Prof. Noor Nieftagodien, Professor of History, Wits, and chair of History workshop; Linda Chernis, archivist at GALA and Dr Caio Simoes De Araujo, expert on Lusophone Africa and until recently employee of Wits.

We also invited Dr Hannah Ishmael, archivist at Black Cultural Archives London; Dr Semih Çelik, founder of ArchiveIST; Prof. Elena Isayev, PI of Imagining Futures; Dr Aoife McNeice O’Leary, project fellow in Imagining Futures; Nicky Nye Library and Information Services, and Annie Price, Special Collections, both University of Exeter.

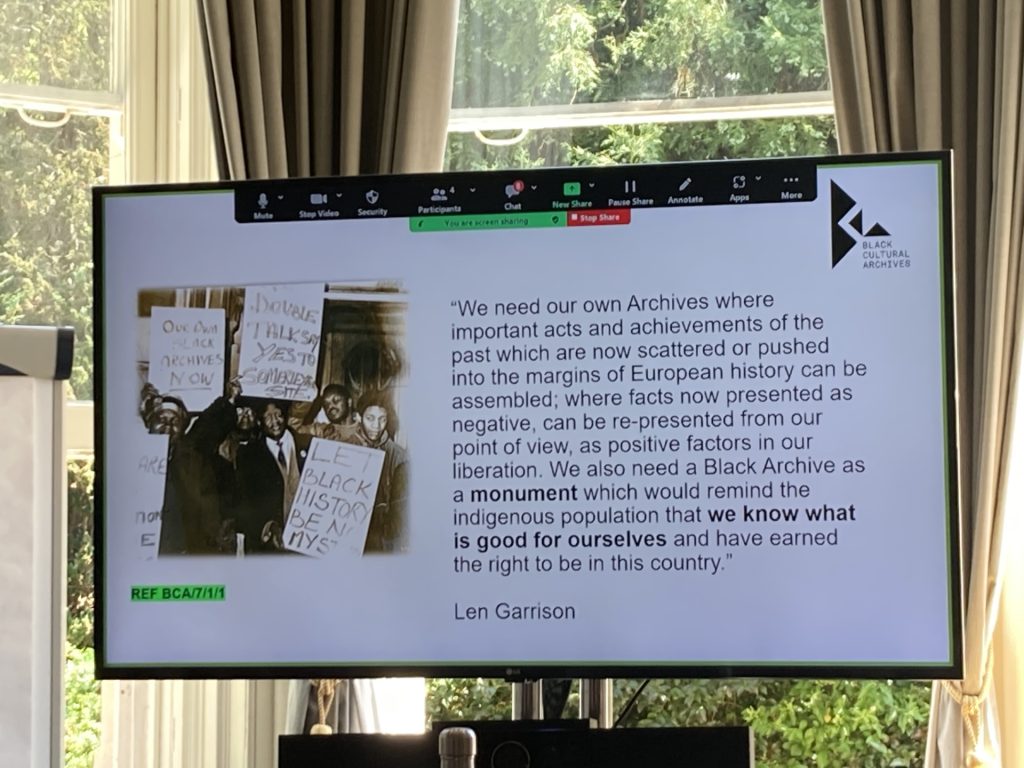

In the course of the discussions Prof. Nieftagodien talked about how it was both difficult and necessary to archive the events of radical movements, how archives do not just record movements but have the capacity to shape them, how History workshop had tried to do that overall decades, and how it proved to be extraordinarily difficult to do so for the Rhodes Must Fall/Fees Must Fall movement. Linda Chernis talked about the activist archive – which reached out, through partnership with artists, to take the archived knowledge to those whose lives it was about. In the case of the Queer communities of South Africa, this represented both joyful and empowering occasions, to be seen and heard and celebrated. On the other hand, Linda alerted us to the dangers of appropriation and alteration, even unwitting, of the voices and visions of already marginalised communities and individuals, through this process, such that the story that is told is not one they would have wanted to tell of themselves. In a similarly critically celebratory spirit Dr Hannah Ishmael told us about the history of the Black Cultural Archives, Brixton, London and the quest of Len Garrison and other founders and contributors to create a space of memory for a community that was denied history and cultural capital.

The tone turned serious as we discussed the dangers of visibility – Dr Semih Çelik, told us about the need to destroy materials in some cases, where such materials could endanger those that had created it. It was even more complex as we travelled further along this route of the duty of care and discussed instances of ethical dissonance. Should the archivist protect the reputation of oral history interviewee, for example, who makes racist or homophobic statements, by redacting these materials? The majority opinion seemed to be against such an approach, and the duty of the archivist being limited to recording what is gathered in all its variety, rather than erasing undesirable elements. There was more involved discussion then, on how such materials should be presented to the public, and what duty of care is owed to the users of the archive.

In Cast in Stone, we are aware that we are ourselves creating an archive. We were therefore both encouraged by this discussion and alerted to the many nuances and implications of our project, and shall continue to think how and in what way an archive can be a public good, especially for those that are under-represented in the calculation of social goods.