By Ghee Bowman

There’s been a lot of conversation in some Exeter circles about the statue of Redvers Buller that stands outside Exeter College, including Alan Lester’s article covering his career and another on the curious practice of coning. This post will record some thoughts on the man and his career, and then move on from the statues that exist already, to discussions of all the other statues and plaques that are yet to be erected.

What I find remarkable about the man Redvers Buller and his legacy is the way that he was both a product and (especially later) a producer of Empire. He fought in so many of Victoria’s ‘little wars’ as detailed by Lester. He was immersed in the imperial principle of loot and plunder, and the so-called ‘punitive expedition’, whereby an African or Asian country could be attacked and looted by a European country with the excuse of inflicting retribution or imposing a lesson on a ‘non-state or a putatively “uncivilized” enemy’ (Ballard and Douglas).

Buller’s first action, at the age of 20, was to participate in the burning and looting of the Chinese Emperor’s Summer Palace, and he there acquired ‘a small share of the spoil as presents for his sisters… Perhaps they were loot; perhaps he bought them at the official auction of treasures’ (Powell). Such spoils were normal, an expected part of the expansion of European empires. But now, how would we view such activities?

Later in his career, Buller was in charge of the ‘prize agents’ after the sacking of the city of Kumase in Ashanti (now Ghana). According to Buller’s biographer and apologist Geoffrey Powell, the quantity of loot was ‘limited only by the scarcity of porters’. In fact, there were 17,000 porters, and the scale of the loot must have been considerable.

The assumptions about empire and its creation that I grew up with at school in the 1970s have largely gone from educational circles, but their influence lingers in the wider British mentality. I wonder if modern Britons were confronted with the reality of Kumase, the Summer Palace and other such ‘expeditions’, what they would make of it. Buller was a man of his time – that is the common refrain when anyone questions his participation and indeed his leading role in bloodshed by the British on people of colour throughout the world. Of course he was, we are all of our time. But did he have no agency? Was he powerless to prevent, to protect, to protest?

But I suggest we put aside the discussion of Buller and his statue. I’m far more interested in the statues and plaques that are to come. Let’s not focus our limited attention on the old grey statues of old grey men, let’s rather celebrate, explore, study and understand the histories of people of colour and other migrants, let’s dig into the local history of empire and of migration and let’s put up new statues and plaques. Let’s balance the imbalance towards dead white famous men – to be praised in the Victorian classroom and church – with some ordinary people, people of colour who reflect the changing nature of our society, who have been long ignored. Stories hidden away in back streets and housing estates, rather than those on show in our public spaces.

Starting in 2013, I have been involved in a project in Devon called ‘Telling our Stories, Finding our Roots’ exploring the multi-cultural history of this rural county. Building on the work of Lucy MacKeith and others, a multi-cultural team of volunteers came together to challenge the notion that ‘Devon is white and always has been’. We found a remarkable array of stories, from the time of the Romans onwards, covering migration into and out of the county, the movement of people and the movement of goods (and of people who were treated like goods). Here are some examples of the stories we found, all of whom could be remembered with a new statue.

Image credit: Ghee Bowman / Sue Evens’ collection.

Dorothea Hendy was born in 1911 in St Austell, the daughter of a Black Jamaican sailor and a White Cornishwoman. She moved to Exeter in 1939 and stayed here for the rest of her life. During the war she worked at the airfield and recalled the planes and gliders taking off before D-Day, circling like wasps and bees. A Black Briton, she was attacked one evening by white American soldiers stationed here, but found sanctuary with a neighbour who was a fireman. After the war she married and had seven children, and is still warmly remembered in the city. She was an extraordinary ordinary woman, one of thousands. A recent decision to install a statue of Lady in Blue on the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square shows the public demand for women like Mrs Hendy to be remembered. Perhaps Exeter’s “civic fathers” are listening.

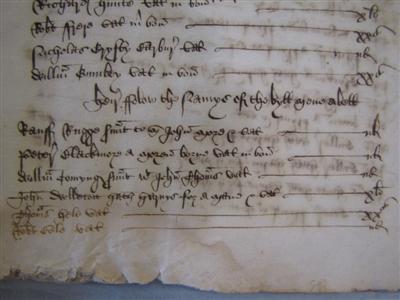

Image credit: Ghee Bowman / Devon Record Office.

Another story that came to light during the ‘Telling our Stories’ project was of Exeter’s first Black resident. Henry VIII’s military survey of 1522 commanded the constables of each parish in England to conduct a census of the men in the parish, whether they had the arms and armour they were supposed to, and their wealth (imagine if a twenty-first century census asked us that!). Among the male population numbering just 1,363, a remarkable 64 were classified as ‘aliens’ – born outside the country. That’s around 5%, a level not achieved again until late in the twentieth century. Among the Flemings, Bretons and Italians was a man living in St Petrock’s parish, at the west end of the High St. His name is recorded as:

‘Peter Blackmore, a moren borne is worth in goods nil’ (Rowe)

The survey was not for guests or visitors, but for residents. So Peter Blackmore is our first recorded Black resident, over 500 years ago. As Miranda Kaufman has shown, there were many Black folk in England in Tudor times. As this was before Devonian John Hawkins decided to sail to Sierra Leone and take African men ‘partly by the sword and partly by other means’ across the Atlantic to Hispaniola, Peter Blackmore was as much a free man as any other alien in Exeter (Gray). We know nothing more about him, but his presence indicates a forgotten diversity that is worth remembering. St Petrock’s church still stands, serving now as a centre for local homeless people. Perhaps they will find a place for this Tudor alien on their walls.

Image credit: Ghee Bowman / Devon Record Office, s757/DEV/TUC.

Another story is of somebody who spent no more than 90 minutes in Exeter, but left a lasting impression on those who met him. In July 1868, a ship called HMS Urgent moored at Plymouth, bringing as a hostage a seven-year old boy. This was Prince Alemayehu Simyen Tewodoros, son of the Emperor of Ethiopia, recently defeated by the British in another punitive expedition. Alemayehu was travelling to the Isle of Wight to meet the Queen, and he changed trains at St Davids. The word got round, and a little court assembled in the First class refreshment saloon, including a reporter from the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette and a local artist by the name of Tucker. Tucker sketched the boy in his blue jacket and straw hat, and the charming picture resides in our local record office.

The prince spent the rest of his life in England, and was deeply unhappy, dying an early death at the age of just 18. For an hour and a half he stopped at Exeter, and perhaps his ghost haunts the saloon still.

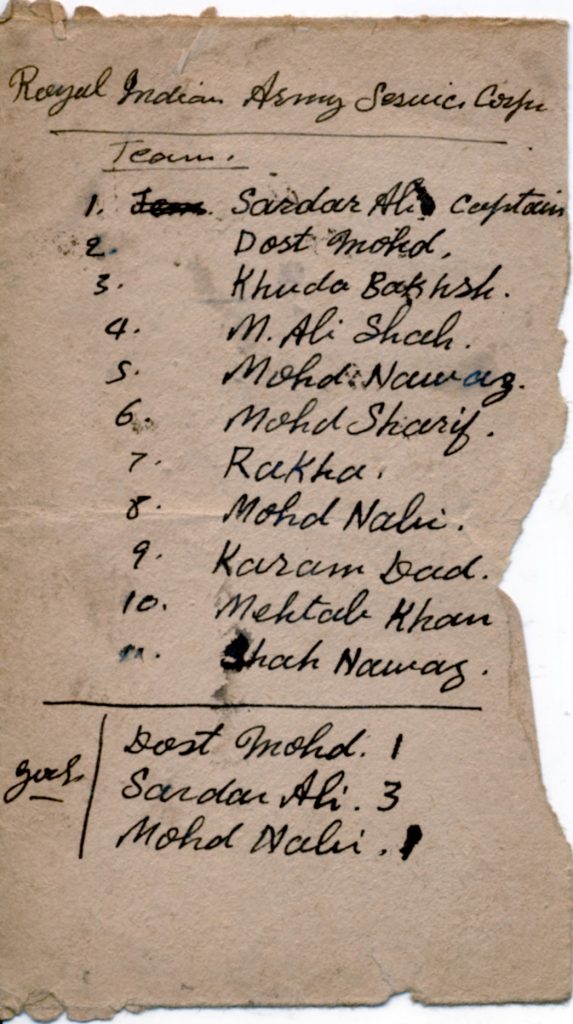

Image credit: Ghee Bowman.

One final story will suffice. In the Autumn of 1940 Devon played host to soldiers of the Indian Army. These men had been part of the British Expeditionary Force in France, retreated to Dunkirk and were taken off the beaches (Bowman). Some landed at Plymouth, and many more were stationed in South Devon, at Kingsbridge, Shaldon and elsewhere. They marched in parades in Torquay, Exeter and Plymouth, and their special hospital was set up in Plymouth until bombed out in April 1941. While a detachment was at Woodleigh monastery, they were invited to play hockey against a local youth club. 75 years later the son of the youth club leader recalled:

After the match in which the Indians scored four goals, both teams trooped off to The Cosy Café for tea and I went along with my parents to join them. I remember them being calm, polite and very pleasant men and I was certainly included in their company. My Dad managed to find an envelope which he opened out and asked them to list the members of their side which one of them did. (Caseley)

Image credit: Ghee Bowman / Patrick Caseley.

These men stayed for a year or so in Devon, but the memory lingered for all of Patrick Caseley’s life. With the recent dedication of a new memorial to these men in Kingussie in the Scottish Highlands, the challenge has been made to other parts of the UK to remember them.

There are currently no statues and no plaques to people of colour or migrants in Exeter. Plymouth recently installed a statue of Jack Leslie outside the football ground, celebrating a man who scored 133 goals and was called up to play for England, but never allowed. In Exeter there is a gap, an absence to be filled, something like our own fourth plinth. Is it time this city progressed from grey horsemen with cones on their heads to something more vibrant and more reflecting our increasingly multi-cultural city?

Bibliography

Ballard, Chris, and Bronwen Douglas, ‘“Rough Justice:” Punitive Expeditions in Oceania’, Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, 18, 1 (2017)

Bowman, Ghee, The Indian Contingent: The Forgotten Muslim Soldiers of Dunkirk (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2020)

Bowman, Ghee, Kalap, Hilda, and Redfern, Nicole, ‘Telling Our Stories, Finding Our Roots, Devon’s Multi-Cultural History’ <https://www.tellingourstoriesdevon.org.uk/>

Caseley, Patrick, ‘Email from Patrick Caseley to Ghee Bowman’, 18 August 2017

‘Exeter researcher rediscovers unique story of an African prince in Exeter’, University of Exeter Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, 7 June 2022 <https://arabislamicstudies.exeter.ac.uk/newsandevents/archive/articles/title_915345_en.html>

Gray, Todd, Devon and the Slave Trade (Exeter: The Mint Press, 2007)

Heavens, Andrew, The Prince and the Plunder: How Britain Took One Small Boy and Hundreds of Treasures from Ethiopia (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2023)

Kaufmann, Miranda, Black Tudors: The Untold Story (London: Oneworld Publications, 2018)

Khomani, Nadia, ‘“Everywoman” and Horse Sculptures Chosen for Display at London’s Fourth Plinth’, The Guardian, 15 March 2024 <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/mar/15/everywoman-and-horse-sculptures-chosen-for-display-at-londons-fourth-plinth>

‘King Theodore’s Son at Exeter’, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 17 July 1868

Kumah, Jenny, ‘Jack Leslie Statue Unveiled at Plymouth Argyle’, 2022 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-devon-63158563>

Lester, Alan, ‘Redver Buller’s Empire’, 2023 <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2023/08/22/redver-bullers-empire/>

MacKeith, Lucy, Local Black History: A Beginning in Devon (London: Archives and Museum of Black Heritage, 2003)

Maddinson, Tommy, ‘Colonial Statues, Public Space and Masculinity in Postcolonial Britain’, 2023 <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2023/12/12/colonial-statues-public-space-and-masculinity-in-postcolonial-britain/>

‘Memorial To Members Of Force K6 Unveiled In Kingussie’, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 2022 <https://www.cwgc.org/our-work/news/memorial-to-members-of-force-k6-unveiled-in-kingussie/>

‘Mrs Hendy of Wonford’ <https://www.tellingourstoriesdevon.org.uk/exeter-archive/1944/mrs-hendy-of-wonford>

Patterson, Ryan, ‘The Third Anglo-Asante War, 1873–1874’, in Queen Victoria’s Wars: British Military Campaigns, 1857–1902., ed. by SM Miller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 106–25

Powell, Geoffrey, Buller: A Scapegoat? A Life of General Sir Redvers Buller VC (London: Leo Cooper, 1994)

Rowe, Margery, ‘Tudor Exeter – Tax Assessments 1489-1595, Including the Military Survey 1522’, Devon and Cornwall Record Society, New Series, 22 (1977)

The Jack Leslie Campaign, <https://jackleslie.co.uk/>

Tucker, Portraits of Devonshire Characters, Devon Record Office, s757/DEV/TUC, <https://www.tellingourstoriesdevon.org.uk/blog/2021/tuckers-sketches>