Introduction

The statues mapped across Britain and France as part of the Cast in Stone project have frequently been the source of controversy for their links to slavery, colonialism and racism. In this blog post, however, I would like to use colonial statues to open up a different set of conversations arounds gender and masculinity in postcolonial Britain. For if ‘everyday life is an arena of gender politics, not an escape from it’, as R. W. Connell put in in their pathbreaking work Masculinities (2005), then we need to interrogate public space as a key site in which masculinities, old and new, are represented, performed, and negotiated with across contemporary British life.

At first glance, this seems like a fairly simply task. Most statues across Britain are overwhelmingly depictions of white heterosexual men from the nation’s past. In 2018, the Public Monument and Sculpture Association listed 174 female statues out a total of 828 recorded statues, with only 80 of them actually being named women and nearly half being female monarchs (BBC, 2018). Public space in Britain has largely been homogenised and hegemonised by representations of male figures across time: slave-owners, soldiers, politicians, governors, and the like.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to frame public space as singularly masculine, ever-frozen in the nineteenth-century world with the same-old statues of dead white men looming over us today. Rather, public space is always a site of contestation: a site in which identities, like masculinity, are represented, performed, negotiated with, and contested across day-to-day life. There is not one version of a “masculinity” that transcends time and space, but multiple masculinities that have been lived in the past and are being lived as you read this article. We simply can’t draw a line from the nineteenth-century to our twenty-first century present and say that the idea of masculinity has remained essentially unchanged. I doubt to imagine what Victorians and Edwardians would have thought of their latter-day descendants walking past their beloved statues of society’s “great men”, only to dutifully place a stolen traffic-cone on top of their heads!

As such, this article examines three colonial statues – Thomas Hughes, Herbert Kitchener, and Redvers Buller – and their wider histories to complicate how we understand this relationship between statues, public space, and masculinity. While the statues of Hughes, Kitchener, and Buller all date from the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the article’s three sections roughly correspond chronologically to the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. Placed in relation to one another, these three statues form a constellation in which we can trace the evolving historical and cultural relationship between colonial statues and masculinity.

I. Thomas Hughes: Public Schools and Muscular Christianity

Image credit: Wikipedia

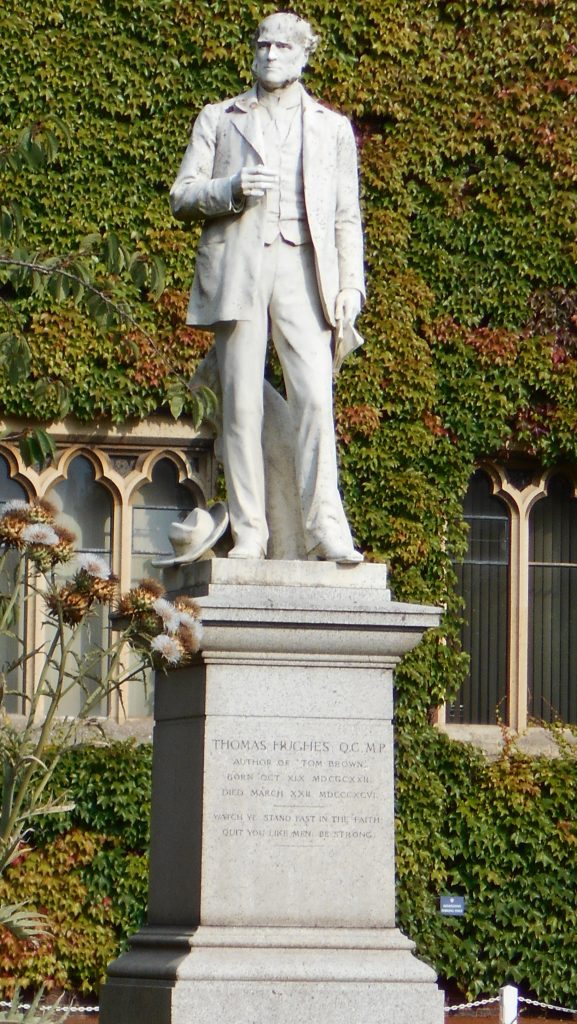

The statue of Thomas Hughes (1822-1896) is located in the grounds of Rugby School in Warwickshire. Created by Thomas Brock (1847-1922) in 1899, the figure of Hughes is made of white marble and stands at a height of roughly 18 feet. Hughes was an ex-pupil of Rugby and had attended the school in the 1830s, when it was under the direction of Thomas Arnold (1795-1842). A lawyer, judge, Member of Parliament, and author, Hughes is most well-known for his book Tom Brown’s School Days (1857). The novel is a recollection of Hughes’s time at Rugby and explores the experience and development of young men in the world of the British public school.

Independent public schools like Rugby were firmly tied up with Britain’s imperial project. In the nineteenth-century, the very life and culture of British public schools was shaped around preparation for imperial service, whether that through the school curriculum, the importance placed on sports and competition within school life, or the hierarchies embedded within the student body itself. C. L. R. James’s classic memoir Beyond a Boundary (1963) examined some of the revolutionary changes that sports like cricket underwent during this period, arguing that Hughes, alongside Arnold and the cricketer W. G. Grace (1848-1915), paved the way for ‘one of the most fantastic transformations in the history of education and of culture’. In response to these histories, several educational institutions across the country have begun their own investigations into their relationship to empire. In 2021, for example, Rugby launched its 5-year project Schools of Empire: Class and Colonialism, c.1750–c.1945, which seeks to explore the historical intersection of education and empire across the themes of class, colonialism, gender, and race.

To tie this back to our discussions of colonial statues and masculinity, Hughes’s statue is noteworthy because his novel Tom Brown’s School Days represents the very genesis of the philosophical movement known as ‘Muscular Christianity’. Muscular Christianity, as George Mosse (1996) describes it, was shaped around the ideal of ‘an aggressive, robust, and activist masculinity’. Through sound moral and physical education in body and mind, achieved through the same physical exercise and Christian instruction to what Hughes had received at Rugby, the sons of England’s public schools would lead the battle against ‘sinfulness, and against those who stood in the way of England’s greatness’ as they went out to into the colonial world. Men entering the colonial service would spread their belief in the importance of physical and religious education, and with it a particular vision of what proper “masculinity” should be, to Britain’s colonies. Peter Alegi (2010), for instance, has traced the introduction of muscular Christianity in colonial Africa through football as part of a wider history of the sport on the continent.

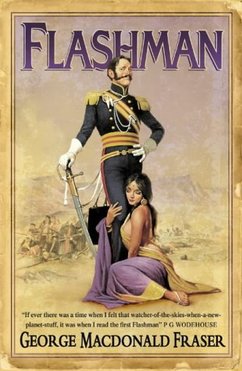

Hughes and Tom Brown’s School Days continue to have a lasting impact on normative ideals of masculinity today. One such example is George MacDonald Fraser’s series of books titled The Flashman Papers (1969-2005), based on Hughes’s original Harry Flashman character, which recounts the privately-educated Flashman’s various colonial adventures, along with an extremely misogynist narration of his various “sexual conquests” across the globe. More recently, the emergence of what has been called “gym bro” culture (Ewoma, 2023) points to the enduring legacy of the muscular Christian ideal today, and the value it places on a particular aesthetic as confirmation of one’s male identity.

II. Herbert Kitchener: Your Country Needs You!

Image credit: Wikipedia

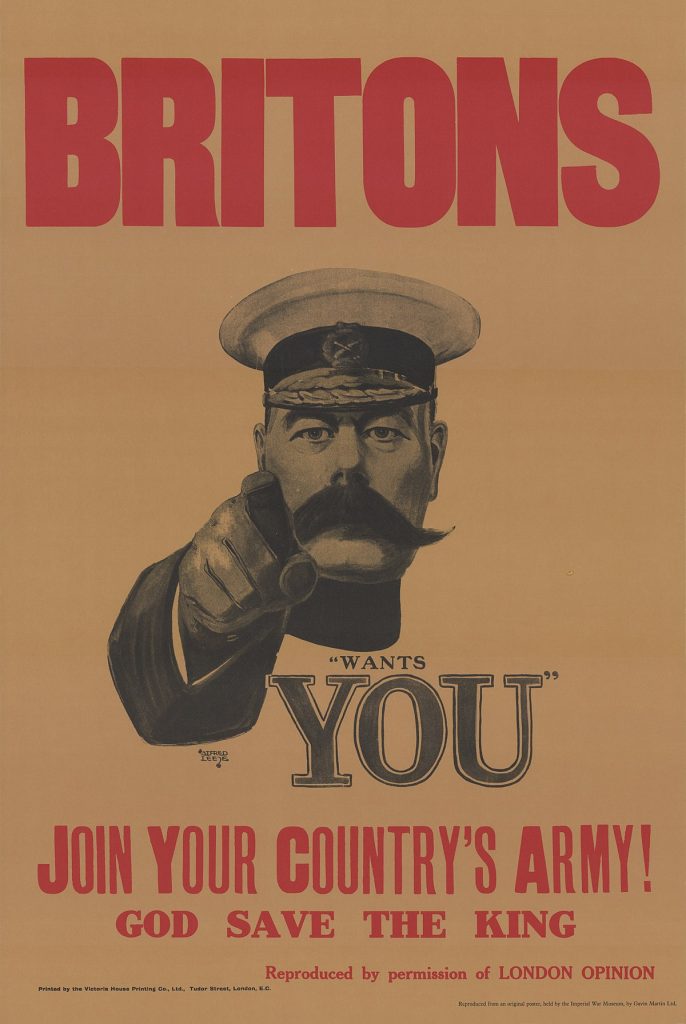

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener (1850-1916) is the iconic figure of the First World War advertising poster, “Lord Kitchener Wants You”, in which Kitchener points directly at the viewer and asks them to enlist in the British Army. Kitchener was one of the most significant military and colonial figures in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Britain, serving in Egypt, Sudan, South Africa and India. During the Second Boer War (1899-1902), Kitchener was responsible for the British Empire’s use of concentration camps and scorched-earth tactics against the Boers. In August 1914, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War and served until his death in June 1916.

Of the many memorials to the man across the country, I would like to concentrate specifically on the statue of Kitchener mounted on a horse in Chatham, Kent. This bronze statue was originally erected in 1912 in Kolkata, India and was sculpted by Sidney March (1876–1968). In 1920, it was moved to Khartoum, Sudan, before being relocated to Chatham in 1959 after Sudan had declared its independence from Britain. It currently lies on Khartoum Parade, near to Chatham’s historic dockyard and the Royal School of Military Engineering. In June 2020, various petitions were launched to Medway Council on whether the statue should be removed or kept in place.

Kitchener’s statue in Chatham is significant from a gendered perspective, not least because his bronze depiction captures so many different aspects of masculine representations that were hegemonic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. Sat upon his horse and with a (phallic) sword placed firmly by his hip, Kitchener’s statue embodies the-then masculine ideals of male chivalry, knighthood, and honour. Kitchener looks out stoically, with no trace of emotion upon his face, and his full regalia and medals indicate to us that this is a man whose identity is fundamentally bound up with the military. As is so often the case with colonial statues, however, there is more than meets the eye at first glance. Kitchener’s status as a life-long bachelor and his alleged homosexuality, for instance, have been the subject of much biographical debate among historians (Faught, 2016).

Image credit: Wikipedia

Two further points are worth picking up on here. The first is the date of the statue’s creation: 1912. The First World War has not yet begun, but there is a real sense here of this depiction trying to salvage a particular form of masculinity on the cusp of disappearing. Mosse has described the fin-de-siècle period, roughly from the 1870s to the War, as the age of ‘masculinity in crisis’, where ‘the enemies of modern, normative masculinity seemed everywhere on the attack’ by the increasing visibility of ‘”unmanly” men and “unwomanly” women’. Kitchener’s immortalisation in the advertisement “Lord Kitchener Wants You”, along with posters like “Daddy, What Did You Do In The Great War?” (1915), played on these anxieties by identifying military service with confirmation of one’s “manhood”.

The second is the statue’s journey from Kolkata, Khartoum, and finally to Chatham. Kitchener may have had one life, but this statue has had three: a life in colonial India, a life in colonial Sudan, and a life in postcolonial Britain. More archival work needs to be done to explore the statue’s precise historical trajectory across the twentieth-century, but it is interesting to reflect on how colonised male subjects in India and Sudan, as marginalised masculinities negotiating public spaces, might have responded to this figure of Kitchener and the particular representation of white hegemonic masculinity it so firmly embodies.

III. Redvers Buller: “Coning” Statues and the Carnivalesque

Image credit: Lewis Clarke / Exeter CIGH

On the corner with the reprobates

That you will call your mates for all the years you’ll waste

This toxic masculinity

It’s all that I can see in floods of thirsty streets

‘Friday Fighting’, Sam Fender

Alan Lester (2023) has already written an excellent blog post on the history of Redvers Buller (1839-1908) and his statue in Exeter, so I will refrain from going over the terrain already covered by him. I am less interested in Buller-the-man and his biography, and I want to concentrate instead on the unique and slightly bizarre trend of Buller’s statue sometimes having a traffic cone placed on the top of its head. This particular trend is local to Exeter, but it has been repeated elsewhere with statues like the Duke of Wellington in Glasgow, Queen Victoria in Leamington Spa, and even Kitchener himself. “Coning”, as we might call it, is a frequent ritual feature of twenty-first century British youth culture, whereby young people steal traffic cones on a night out and occasionally end up putting them on top of a statue. Climbing on top of statues, while perceived as being comedic, is highly dangerous and can end in tragedy: in 2017, a young 18 year old boy sadly died after falling from Buller’s statue and sustaining serious injuries.

“Coning” can be described as a carnivalesque act. First analysed as a genre by Mikhail Bahktin in Problems of Dostoevesky’s Poetics (1999), Bakhtin defines the carnival as a moment in which authority is up-ended by the joyful and free encounter of different peoples, who challenge and defy societal symbols of the profane and sacred through acts of irreverence and subversion. He describes it as a point in time where ‘the laws, prohibitions, and restrictions that determine the structure and order of ordinary, that is noncarnival, life are suspended’.

Bakhtin’s concept of the carnival is especially pertinent here to understanding the relationship between “coning” colonial statues and contemporary youth masculinities in British society. “Going on a night out” is a ritual feature of university life in Britain; a time in which young people, now free from the authority of their parents and teachers, can meet new people, drink legally for the first time, and discover their sexuality. There is a real underside, however, to this contemporary youth culture: students are often forced by their peers into ‘hazing’ rituals, they frequently hurt themselves drinking in order to “prove” their “coolness” or “masculinity”, and there is a serious problem of rape-culture across the British university system as a whole.

For many male British students, the “night-out” is that moment in which they seek to establish their male identity. The night club is the formative space for this, but the practice of “coning” suggests that statues, as public spaces, provide another equally important site. Clambering on a statue and placing a cone on its head is not just a moment of drunken antics, it is a chance for men to perform their masculinity in a unique manner. In the whirl and chaos of a night-out, where strangers are encountered and friends are made, “coning” offers young men the opportunity to show off their risk-taking and bravado by undertaking a dangerous act. Their plucky placement of a traffic cone is a rebellion against the symbols of authority, society, and the old embodied by the colonial statues that lie across contemporary British towns and cities. The Empire is long since dead – Virginia Woolf (1924) recognised as much nearly a century ago – and so the young Britons of today hardly look up to colonial statues as masculine ideals, but instead see these public spaces as sites for enacting their own masculine identity.

“Coning” as a carnivalesque ritual suggests how masculinity as a societal norm has evolved across the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, as well as symbolising the tragic-comic ways in which masculinity is negotiated with in contemporary British youth culture. It reminds us that not only is our racialised and gendered public space constantly being contested, but that politics and culture, as Stuart Hall (1988) put it, is all about production: the production of new subjectivities, new identities, and new ways of being in the world.

Conclusion

By now, the complexity of the relationship between colonial statues, public space, and masculinity should now hopefully have become clearer to the reader. By juxtaposing and interrogating three male statues in modern Britian, all of which date from a similar time period and have their own colonial connections, we can see how the histories of their personal lives and of their statues illuminate an array of information about the historical and cultural evolution of masculinity across the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. Sharing distinct and overlapping historical trajectories, the statues of Hughes, Kitchener, and Buller each capture powerfully the intricacy of male subjectivities across the colonial and postcolonial worlds. Statues of men may dominate public space in Britain, but ordinary people are always navigating, negotiating, and contesting these racialised and gendered spaces in the contemporary present. Historical time, as Iain Chambers (2010) writes so poignantly, is never empty, homogenous, and fixed. Instead, it is filled with ‘intervals, irruptions, and interruptions’: explosive moments in which our colonial past and postcolonial present come together in a dialectical flash, and remake the world in a new image each time.

Bibliography

Internet resources

Drummond, Michael, and Cohen, Sonny, ‘The story behind the Chatham Lord Kitchener statue – and why people are so angry’, Kent Live, June 11 2020, accessed from <https://www.kentlive.news/news/kent-news/story-behind-chatham-lord-kitchener-4214568> [accessed December 12 2023]

Ewoma, Martyn, ‘How ‘Gym Bro’ Culture is Harming Young Men’, Dazed, May 4 2023, <https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/59789/1/how-gym-bro-culture-is-harming-young-men> [accessed December 12 2023]

Fender, Sam, ‘Friday Fighting’, YouTube, July 25 2018, accessed from <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVSIhm7rvjo> [accessed December 12 2023]

‘Reality Check: How many UK statues are of women?’, BBC, April 24 2018, accessed from <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-43884726> [accessed December 12 2023]

‘Rugby. Thomas Hughes Statue’, Our Warwickshire, accessed from <https://www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/catalogue_wow/rugby-thomas-hughes-statue> [accessed December 12 2023]

‘Schools of Empire: Class, Race, and Colonialism, c.1750-1945’, accessed from <https://schoolsofempireproject.co.uk/> [accessed December 12 2023]

‘Why Do People Put Traffic Cones on Statues?’, BBC, November 13 2013, accessed from <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-24925296> [accessed December 12 2023]

Books

Alegi, Peter, African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2010)

Bakhtin, Mikhail, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, ed. and trans. by Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999)

Berger, John, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin Classics, 2008)

Berger, Maurice, Wallis, Brian, and Watson, Simon, eds., Constructing Masculinity (New York; London: Routledge, 1995)

Butler, Judith, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006)

Faught, C. Brad, Kitchener: Hero and Anti-Hero (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2016)

Chambers, Iain, ‘Maritime Criticism and Theoretical Shipwrecks’, PMLA, 125, 3 (2010) 678-684

Connell, R. W., Masculinities (Berkley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2005)

Gramsci, Antonio, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, trans. and ed. by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2003)

Hall, Stuart, ‘Gramsci and Us’, in The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left (London: Verso, 1988)

Hall, Stuart, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Milton Keynes: Open University, 1997)

hooks, bell, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love (New York: Washington Square Books, 2004)

James, C. L. R., Beyond a Boundary (London: Hutchinson, 1963)

Mosse, George L., The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996)

Woolf, Virginia, ‘Thunder at Wembley’, Nation and Athenaeum, June 1924