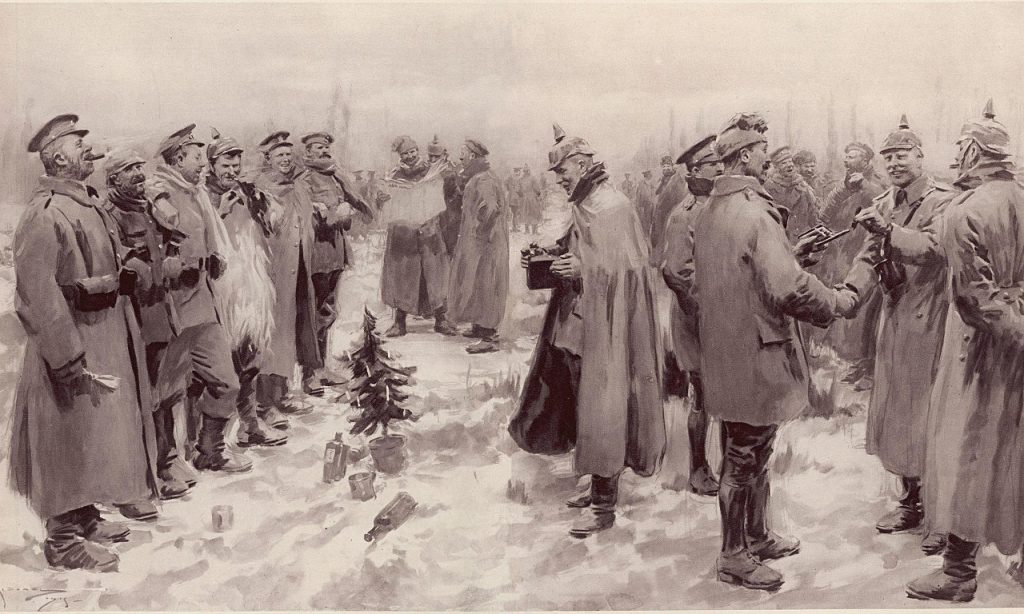

The Illustrated London News, January 9 1915.

Image credit: Wikipedia

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Matthew Arnold

What has been called the “culture war” is – sadly – an unavoidable topic for those of us writing about the history of the British Empire and its memorials in the present. We are all now in Gramsci’s trenches, stuck in the mud and dirt of a historical and political battlefield whose lines have been sharply drawn. The contemporary historian dare not poke their head out for risk of being hit by the inevitable accusatory bullet: “woke”, “postmodernist”, “critical racist theorist” and the like. On and on the gunfire goes, each side throwing itself against the other to no avail. Schmitt’s twisted conception of the political as divided between friends and enemies threatens to become a reality [1].

Out of the wreckage of the First World War – the archetype of trench warfare – came a two-volume work named Decline of the West [2]. Written by the German polymath Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), Decline of the West was that era’s defining statement of kulturpessimismus, or ‘cultural pessimism’. Spengler, deeply informed by the racist theories of his time, saw the philosophy of history as the product of biological-cultural organisms who evolved and died over time, and gloomily predicted that Western civilisation would enter a period of natural decline in the early twenty-first century. ‘The Hour of Decision’, a later essay by Spengler written in 1934, went on to warn of the threat to Western civilisation from what he termed the ‘coloured world revolution’, in close resemblance to earlier works by white supremacists Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard in the United States [3]. As the events of the Holocaust would tragically confirm, however, Spengler’s wildly disturbing prophecies were not only morally and intellectually bankrupt, but they missed the very barbarism within “the West” itself [4].

Yet a century later, and it is frightening just how much Spengler’s pessimistic thought now animates our contemporary kulturkampf [5]. The titles of some of the books rolling off the shelves speak for themselves: Decline of the West, War on the West, Suicide of the West and so forth. One recent intervention into the historical controversies over British imperialism accuses ‘academic post-colonialism’ of being ‘an ally – no doubt, inadvertent – of Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia and the Chinese Communist Party, which are determined to expand their own (respectively) authoritarian and totalitarian power at the expense of the West’. The ‘very integrity of the United Kingdom and the security of the West’ is purportedly at stake in these debates [6]. The contemporary conflict between Israel and Hamas is now being spun in a similar way, with students and academics implied to be egging on Hamas’s destruction of Israel in pursuit of “anticolonial liberation”. As a recent university graduate of both history and postcolonial studies, and one who has watched the devastation unfolding across Ukraine, Israel, and Palestine with grief, sorrow and horror, the author cannot help but feel a profound unease at the sorts of accusations being made against them.

Any attempt to correct these kind of narratives through careful, thoughtful, and evidence-based historical reasoning seems desperate. The line between genuine historical revisionism, what was once a standard practice of academic life, and historical negationism is becoming increasingly blurred by respectable intellectuals who should know better [7]. One side has already decided its own version of events: the (monolithic) West is in decline, its culture threatened by a fifth column, and only a revitalised national-conservatism can stop the rot from spreading. Any attempt to meaningfully discuss and work through our imperial past only confirms their worst suspicions.

So the sole response the author can offer to Spengler’s inheritors, while it may fall on deaf ears, is a heartfelt plea: lower the temperature. Students are not trying to overthrow “the West” through historical-cultural subversion. As university lecturers will know all too well, even if we were planning to attempt such a ridiculous thing, half of us would have failed to show up to the seminar, and those that did probably would have forgotten to do the assigned readings on Marx [8].

We should also all remember that the contestations over Britain’s history in 2020 took place in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. That year, for each and every one of us, the world changed, fundamentally changed. It became a scary and disorienting place, one in which we were exposed to the cruel reality of our bodies as not only profoundly vulnerable to the air we inhale, but equally capable of harming those around us through the very same air we exhale. All of us lost something in that terrible period, whether that be family, friends, loved ones, or the basic experiences of life itself. Many still live with its long-term health effects to this day. We each carry our own weight from the pandemic.

There are some, looking to soothe the pain and grief of those years, who find a ready outlet in the ongoing culture wars over history. The loss of a world that once felt “safe”, the world before the pandemic broke out, is inextricably bound up with the loss of a world innocent to the histories and memorialisation of empire. Is it not remarkable that the anxious minds of the culture warriors, desperately scanning for “woke” enemies across Britain’s universities, museums, and media outlets, resemble the very same anxieties we once experienced towards the potentially transmissible bodies around us? Is the anger and vitriol they unleash towards students, academics, and others in fact an expression of grief for a world that no longer exists? Are we the same as we thought we were before the pandemic? Judith Butler put it very movingly last year when they wrote:

It is no longer the world that we thought we lived in [9].

So, with this in mind as we enter the New Year, let’s be a little less pessimistic, let’s tone down the rhetoric, and let’s try to be a bit kinder to one another. I’m sure the incredible academics working on the history of empire across this country, who’ve been sheltering in the trenches for some time now, would indeed appreciate a Christmas truce – temporary as it may be.

References

[1] Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, trans. and ed. by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith (London:Lawrence & Wishart, 2003); Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, trans. by George Schwab (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 1996)

[2] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West (1918; 1922)

[3] Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision (1934); Madison Grant, The Passing of the White Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History (1916); Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Tide of Color Against World White-Supremacy (1920).

[4] See Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Spengler After The Decline’, in Prisms, trans. by Samuel and Shierry Webber (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987) 51-73.

[5] For Spengler’s contemporary reception in the twenty-first century, see David Engels, ‘Oswald Spengler and the Decline of the West’, in Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Between the New Threat to Liberal Democracy, ed. by Mark Sedgwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019) 3-21.

[6] Nigel Biggar, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2023), p. 5, p. 7, quoted in Alan Lester, ‘The British Empire in the Culture War: Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 51, 4 (2023) 763-795 (p. 769).

[7] For the original discussion of historical revisionism versus historical negationism, see Henry Rousso, Le syndrome de Vichy de 1944 à nos jours (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1987). The English translation is Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France Since 1944, trans. by Stanley Hoffman (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

[8] For the historical record: throughout their four years at university, the author was not once assigned Karl Marx as a seminar reading by their lecturers. They do confess to owning an abridged volume of Das Kapital on their bookshelves, although like many on the Left they haven’t quite gotten round to starting it yet.

[9] Judith Butler, What World Is This? A Pandemic Phenomenology (New York: Columbia University Press), p. 14.