Roman-style statues are frequently at the forefront of toppling campaigns and contemporary conversations about the role of monuments in upholding or glorifying colonial, Confederate, or capitalist values and ideology. However, the actual style of these statues, and their relationship to other monuments and architecture in their built environment, is rarely cited as a reason for removal. Yet the choice to render colonial statues in a Roman style speaks to the values and ideologies those statues are meant to represent, and reflects a broader tradition of using Classically-inspired or Roman-style architecture and monuments to demonstrate where power lies, and with whom.

In this blog I will examine Roman-style statues and architecture in London as sites of imperial dominance and social exclusion which continue to maintain and empower colonial ideologies and environments today. I will examine three aspects of the relationship between Classical-style architecture and colonialism in London: the role of these statues and buildings in British colonies abroad, their impact in London, and the language of empire they share with other European countries.

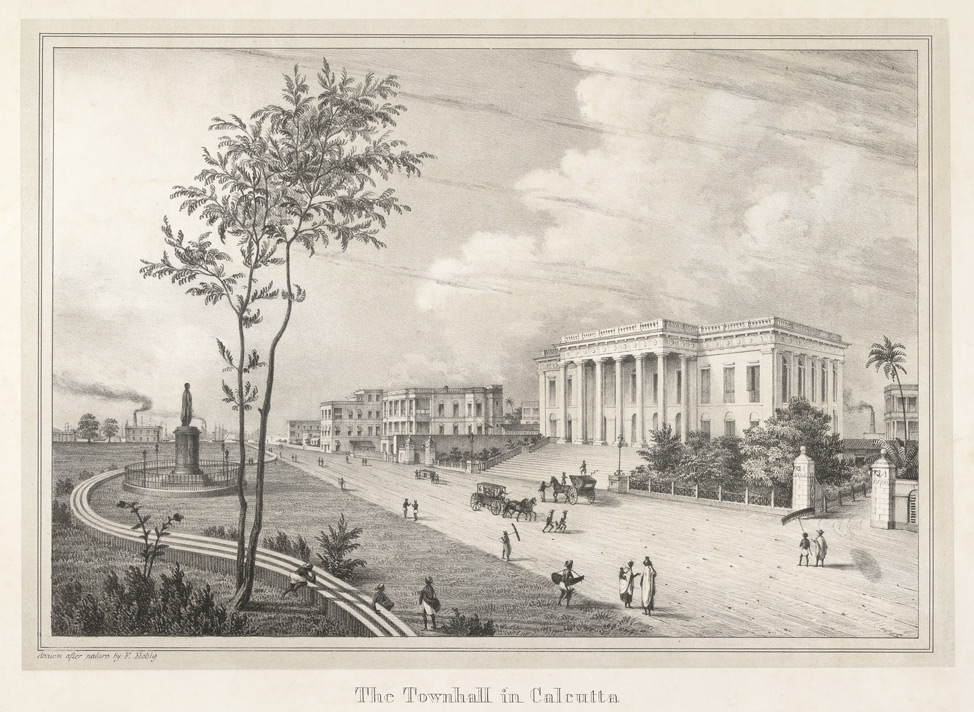

The work of Herbert Baker and Edwin Lutyens, two prominent British architects tasked with rebuilding the British capital of colonial India in Delhi, is a useful starting point to examining the role of Roman-style statues and architecture in British colonization abroad. In a 1914 letter to Lutyens, Baker wrote that the architectural style of the capital-to-be must be considerate of all climates, but above all should “represent the ideal of the British Empire”. He goes on to write that “of course, Classical is the only architectural language that can achieve this”. Neoclassical architecture still abounds in India, including the Secretariat Buildings in Dehli and the Town Hall in Kolkata, which originally included 12 busts of Julius Caesar on the interior and statues of British colonial officials depicted as Roman figures.

Baker’s architectural work in British India followed previous years spent redesigning Cape Town, the capital of British South Africa. Early in his career Baker befriended Cecil Rhodes, who paid for the architect to spend several months taking a Mediterranean tour so that he might be inspired by the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome. Rhodes himself considered the Classics to be an important point of his own inspiration, and following his travels Baker designed the new capital after the Athenian acropolis, building a ceremonial way through Cape Town based upon Roman ruins.

For Baker, Lutyens, and Rhodes, the draw to Classical architecture as a visual language of dominance in the British colonies was not an original ideology, nor was it disconnected from the role of Classics in contemporary British society and politics. In London, it was the colonial administration buildings that were first constructed in a Classical style, such as the India Office buildings (now used as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) which still contain statues of East India Company officials wearing Roman clothing. Atop another building on Whitehall, formerly the Colonial Office, there stood a statue of Britannia in Roman dress seated upon a throne, attended by the Classically-attired figures of Knowledge, Enlightenment, and Power. The colonial officials depicted as Romans used their association with Rome and, by proxy, its imperial legacy, to empower themselves and align their roles within the British empire as a continuation of European colonial tradition.

In eighteenth-century London, the British East India Company’s growing wealth paralleled the increased construction of Classical-style buildings. Where designing these buildings abroad established an imperial vision, within Britain itself this trend signaled a shift away from a standardized national architecture and toward an architecture of empire. Government and administrative buildings, along with central public spaces, came to represent both visually and ideologically the seat of imperial power. Architectural historian Thomas Metcalf writes that “architecture did not by itself, or alone, express the culture of colonialism” but rather “was embedded in a larger system of colonial control”. The Roman-style statues act as part of a larger British system of domination and control. Further, these statues allude to the lasting nature of the Roman empire, whose ruins remain littered across Europe today in a connection between the process of British colonization and the perceived immortality of Roman-style figures and structures. The built environment thus contributes to the perception of colonialism and its associated violences as inevitable or everlasting, a colonizing tactic intended to prevent the conceptualization of other ways of being and world-building.

The role of Latin and Greek study in colonial administration reinforced the narrative of colonial dominance and social exclusion embedded in the Roman-style architecture, both in London and in the British colonies. Appointments to the British colonial service required a strong knowledge of both Latin and Greek, and colonial officers examined for work in British India were asked to write essays in Latin comparing the British and Roman empires as part of their qualifying exams. The social and class divides in which those holding power knew the language of Classical statues and ideology serves as a further point of exclusion for those who are not permitted access. Classical study and statuary represent two aspects of a colonial system created and maintained to articulate where power is held. This messaging endures in Classical-style statues and monuments today, which remain sites of ongoing violence.

In 1913, Buckingham Palace received a new Classical-style facade while Trafalgar Square was rebuilt with Roman-style statuary atop concrete pedestals, centering a towering Roman-style corinthian column crowned by Lord Nelson. These designs “enhanced the position of the king-emperor as the focal point of the imperial system”, and the archway leading between Trafalgar and Buckingham reinforced “the imperial vision that defined the enterprise”. The entire complex remains today, where tens of thousands of tourists view the renovated facade of Buckingham and turn to walk down the intended imperial way, through the arch, and into the open abyss of Trafalgar Square, ringed with Roman-style buildings formerly dedicated to colonial administration and looking up to the Roman-style statues of former colonial officials. The imperial way, the architecture, and the statues all empower one another, suspending time in the implied sense of continuity between empires of the past and present, drawing upon imperial traditions to justify and legitimize the empire at home.

These colonial administration buildings and statues were sites of violence before they resembled any particular architectural tradition, and the particular violences inflicted across different areas of the British empire, including in Britain itself, are not predicated on the presence of Classical-style architecture. However, the presence of Classical-style statues draws upon an existing language and lineage of exclusion and oppression. In the United States, statues of Roman emperors appear across college campuses and public parks, while Roman-style statues of Confederate generals and Columbus remain littered throughout city streets. These statues exert a “sense of ownership rights” tied to public space, and assert the authority of those depicted over the people and place where the statue stands. The statues further act as a claim upon Indigenous land, asserting a white settler history visually and ideologically linked to ancient Rome in an effort to erase Indigenous histories.

In January 2020 a student-led campaign at Brown University sought the removal of two Roman-style statues, recognizing the role of these statues in ongoing settler colonial violence. The statues were brought to campus in 1906 and 1908, two years in which the greatest number of Confederate monuments were built across the US; many of these Confederate statues were based on the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius replicated on Brown’s campus. Both of Brown’s statues would have been immediately recognizable as partaking in the same visual ideology of colonialism and white supremacy, and a core argument for their removal lay in their idealization of white, western civilization.

Best illustrating this point is the immediate and intensive response from alt-right groups in response to the statue removal campaign. Dozens of right-wing publications in the United States, Italy, and Russia defended Brown’s Roman-style statues as “civilizing” and equated their removal with the destruction of “western culture”, while the Wall Street Journal dismissed the campaign as “nonsensical” and the statues as “representing some of civilization’s greatest virtues”. Alt-right groups launched extensive harassment campaigns doxxing the students calling for the statues’ removal with their full names and assumed immigration statuses published alongside defenses of Kyle Rittenhouse and arguments that “white men are being erased from countries they founded”. The relationship between these Roman-style statues and ongoing colonialism in the United States is implicit to contemporary right-wing ideology, and the wave of publications targeting the Brown campaign, each with thousands of comments and shares, goes beyond an articulation of these statues’ white, colonial power. Roman-style statues in the United States operate as a “permanent, physical dog-whistle that avowed white supremacists will readily recognize”, and continue to be the focal point of right-wing violence as well as the symbol of white supremacist groups across Europe and North America. In Britain, as in the United States, these statues partake in a sanctioned discourse of power, setting a certain narrative of power and authority in stone.

Further motivating the construction of Classical-style statues and architecture in Britain was the pursuit of imperial legitimacy in the eyes of mainland Europe. Britain sought to signal through its use of Classical statuary, architecture, and symbols that it could compete in the game of growing empires. This colonial style of building was already associated with particular political ideologies, and would be recognizable to other European colonizing empires — many of whom used similar fashionings to justify and legitimize their own violent and extractive colonial practices while emphasizing control over the colonized populations.

Roman-style statues, monuments, and buildings in London are part of a cohesive and explicitly colonial exercise of power. The neoclassical statues and architecture surviving in Britain today should be understood as “modern monuments to a set of values and political stances which existed when they were commissioned”, colonial both for the figures and ideologies they depict as well as their “explicit purpose [to] represent empire itself”. Their maintenance and display continues to act upon the British population as a demonstration of where power lies and who is allowed to access it. Calls to topple these statues are often met with cries about the erasure of history, but this outrage and fear is ultimately tied to the perceived destruction of power, and the reality that dismantling a built environment of colonialism is never limited to a symbolic gesture. Roman-style statues and architecture should not occupy the forefront of present-day toppling movements and critical conversations only because of the figures they depict, but rather because their style is itself a component of their colonialism, empowering and drawing power from ongoing colonial violence and exclusion in Britain and around the world.

Citations

Brynn, A., Malik, J., Mayeda, O., Kimball, S., and Tackett, K. (2020) “All Roads Lead to Removal”, The Blognonian. October 17, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20201101045351/http://blognonian.com/2020/10/17/all-roads-lead-to-removal-replacing-two-statues-and-redefining-campus-space-at-brown/.

Bocchi, Alessandra. “Ancient History is not Colonialism”. Wall Street Journal. November 30, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ancient-history-isnt-colonialism-11606776241 (Accessed November 30, 2023).

Han, J., Brynn, A., Kimball, S., Hood, K., and Wells, Abby. “Roman Bronzes as Settler Colonialism: Archaeologists and classicists for monument removal”, The College Hill Independent. November 6, 2020. https://www.theindy.org/article/2162.

Hilton, John. “Cecil John Rhodes, the Classics and Imperialism”. In Classical Confrontations, edited by Grant Parker, 55-87. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2017.

Hu, B., Tackett, K., and Malik, J. “The Statues Must Go: Brown Should Not Celebrate Colonialism”, The Brown Daily Herald. November 1, 2020. https://www.browndailyherald.com/article/2020/11/the-statues-must-go-brown-should-not-celebrate-colonialism#:~:text=It%20is%20impossible%20to%20forget,decolonial%20movements%20at%20Brown%20today.

Metcalf, Thomas. An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Monteiro, Lyra. “Power Structures: White Columns, White Marble, White Supremacy”. Intersectionist-Medium. October 27. 2020. https://intersectionist.medium.com/american-power-structures-white-columns-white-marble-white-supremacy-d43aa091b5f9

Vasunia, Phiroze. The Classics and Colonial India Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.