Writing about colonial statues, the biographies of their depicted subjects, and acts of contestation in the present can often feel like a gloomy affair. Of the numerous individuals recorded in the Cast in Stone database, we find types such as slave-owners, slave-traders, colonial administrators, race scientists, war criminals and the like. Many of these men – and they are almost always men – inflicted serious pain, trauma, and death on ordinary people through acts of physical and epistemic violence during their lives. In drawing attention to the enduring legacies of such violence and the historical erasure embodied by such memorials to these “great men”, acts of anti-racist protest against statues often take an equally serious and sober tone: words of indictment are scrawled on their plinths, placards listing their crimes are affixed to their bodies, and blood red graffiti is splashed all over them.

Popular protest against statues needn’t always be so sad and heavy however. In June 1979, for instance, black Zimbabweans celebrated their triumph over white-minority rule by placing a sign saying “THIS SPACE TO LET” in the hands of Cecil Rhodes’ statue in Salisbury. Churchill has had a green mohawk dutifully placed upon his bald head, and if you happen to be a certain well-known “Milk Snatcher” in Grantham, you can expect a welcome egg thrown in your face from time to time.

So, in the spirit of such interventions, this blog post looks at the power of laughter and comedy in destabilising the meaning of colonial statues. More specifically, it focuses on Richard Westmacott’s scantily-clad Wellington Monument in London as an early example of how an imperial statue, intended as a model symbol of civic masculinity, could be immediately subverted upon its unveiling through widespread public ridicule.

“Man O’Metal!!!” … or, how not to unveil a statue

The Wellington Monument in London – not to be confused with the phallic Wellington Monument in Somerset – is a colossal, 18 foot tall bronze statue of Achilles in the south-east corner of Hyde Park, erected in 1822 as a memorial to Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. The colonial connections of the statue are not immediately apparent to the viewer, but they are there. The inscription on the base of the statue, for example, refers to Wellington’s victories at Salamanca, Vittoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo, but is silent on his previous involvement in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1798-99) in India. The sculptor of the monument, Richard Westmacott, has his own imperial links too. Westmacott’s wife, Dorothy Wilkinson, was born in Jamaica and was the daughter of a Dr. William Wilkinson. The marriage may well have introduced Westmacott into elite West Indian circles; indeed, Westmacott produced a number of works for slave-owners and slave-traders throughout his career, including church memorials for Edward Long and Richard Pennant as well as the statue of Robert Milligan for the West India Dock Company.

As Henk de Smaele has argued, Westmacott’s naked statue of Achilles was primarily intended as a ‘symbol of national regeneration’ and civic masculinity after the Napoleonic Wars. Drawing on George Mosse’s idea of ‘the modern masculine stereotype’, de Smaele situates the statue within the broader political and cultural trends of the period, particularly the emergence of the “citizen-soldier” ideal which fused ideas of manhood, nationalism, militarism, and democratic citizenship together. Moreover, as only women were permitted to contribute to the statue’s funding, the memorial took on an ever greater gendered significance by enshrining Wellington as a model patriarchal figure for the “Ladies of England”.

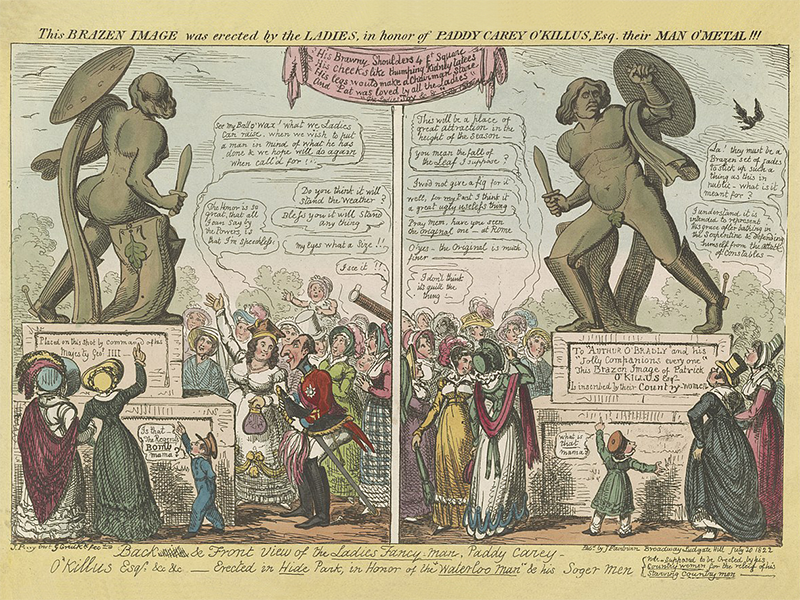

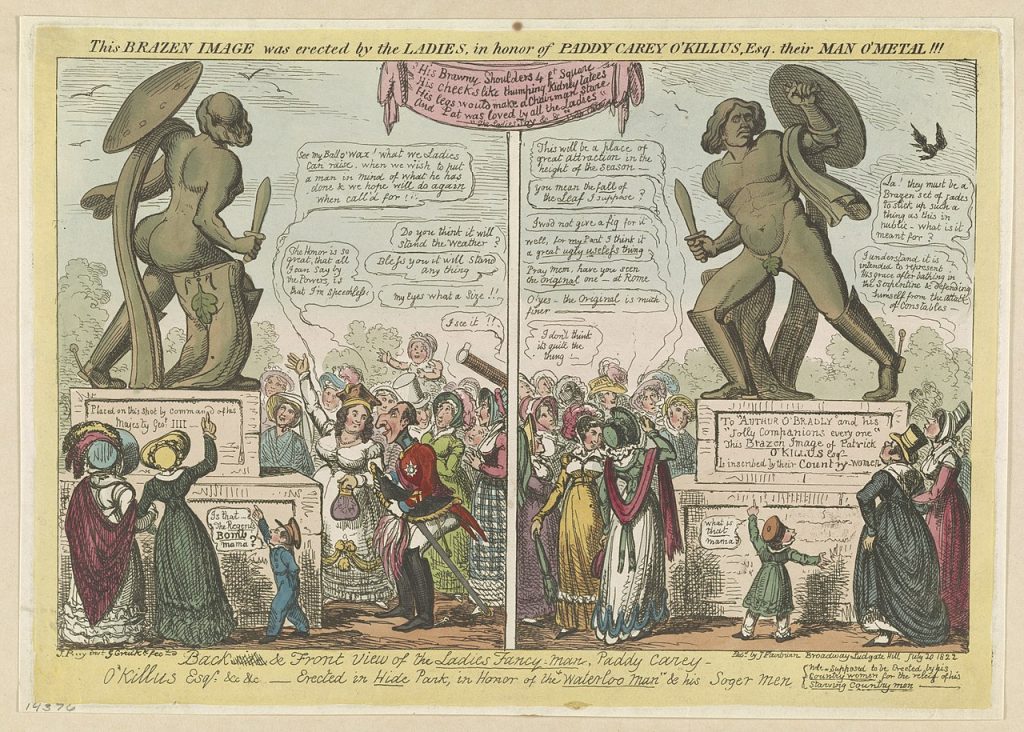

Of course, for those that know the myth, Achilles has his own famous point of weakness. The Wellington Monument could not escape the same fate as its Greek hero. Its own Achilles heel was laughter. The moment it was unveiled on June 18th, 1822, many people simply broke out laughing. Once on display, the statue quickly became a source of ridicule and amusement for passers-by in London, which was visually captured by George Cruikshank in his caricature Backside & Front View of the Ladies Fancy-man, Paddy Carey.

Paddy Carey (1822). Digitised by the Library of Congress.

Cruikshank’s caricature shows a crowd of women and children, accompanied by Wellington himself, gazing at the statue and making humorous remarks about the nude male body on display. The fig leaves covering Wellington’s front and rear are one particular site of comedy, with one lady pondering upon what will happen with ‘the fall of the Leaf’ come autumn. In the left image, an unseen spectator looks on with a telescope, accompanied by speech bubbles reading ‘My eyes what a Size!!! I see it!!’.

de Smaele calls the reaction to the statue a ‘crisis in representation’. In other words, the intended meaning of the Wellington Monument – a proud symbol of civic masculinity – had quickly become undone by its spectators, who made a mockery of Westmacott’s vainglorious male nude. The effect was clearly severe: there are hardly any other colonial statues across the UK so bold in their depiction of the neoclassical male body (indeed the Monument is Grade 1 listed – perhaps Historic England were worried about preserving the fig leaf). In turning the nude male body into an object of satire and ridicule, the laughter of ordinary people had profoundly destabilised an imperial statue intended to embody the heroic citizen-soldier ideal.

Reclaiming laughter today

Of course, we equally need to recognise the limitations of comedy when it comes to disrupting colonial statues. As comedic as George Cruikshank’s caricature of the Wellington Monument is, we can’t divorce this image from his other abhorrent and viciously racist caricatures, such as The New Union Club (1819). Our laughter at these sorts of vain, overblown memorials is tempered by the memory of the violence these men inflicted on others.

The tension between light-heartedness and seriousness in art and culture was taken up nearly a century ago by thinkers like Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. Both of their positions on the matter were nuanced and defy easy summarisation. Broadly speaking, Benjamin saw laughter, or what he called ‘shattered articulation’, as a revolutionary force, an energy through which the masses could disrobe dictators. Adorno, on the other hand, took a much more critical stance on the resistive potential of comedy, even going so far as to say that laugher, ‘once the image of humanness’, risks becoming ‘a regression to inhumanity’ by making a mockery of the victims.

This critical tension between satire and sobriety is enormously productive in thinking about imperial art and sculpture in our contemporary present. The Wellington Monument may seem a distant and humorous object from our past, but the normative ideals of masculinity it tried to represent are not so distant from us today. The twenty-first century manosphere – which often relies on casual sexist internet humour as a gateway to its more disturbing circles – has reclaimed many of these visions of what the “ideal” male body should look like, driving masculine anxieties around physical appearance into support for misogynist and far-right political movements. The manosphere, as Laura Bates has written extensively about, is no joke: the murders from Isla Vista to Plymouth are testament to that cruel reality. Yet, amidst the contemporary wails over “wokeness” and the decline of the “Western man”, perhaps laughter does have a place in anti-racist and feminist politics today. Comedy has always been and continues to be a powerful weapon throughout history in challenging, subverting, and destabilising images of authority. In any case, there are still plenty of eggs to go around.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Cruikshank, George, Backside & Front View of the Ladies Fancy-man, Paddy Carey (1822), digitised by the Library of Congress, <https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ds.07530/> [accessed 16 March 2023]

Secondary Sources

Adorno, Theodor W., ‘Is Art Lighthearted?’ in Theodor W. Adorno, Notes to Literature, Volume Two, ed. by Rolf Tiedemann and trans. by Shierry Weber Nicholsen, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991) 247-257

Bates, Laura, Men Who Hate Women (London: Simon and Schuster, 2020)

Benjamin, Walter, ‘Hitler’s Diminished Masculinity’, in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings. Volume 2, Part 2 1931-1934, ed. by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, and trans. by Rodney Livingstone and others (Cambridge, MA; London; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005) 792-793

Connell, R. W., Masculinities (Berkley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2005)

de Smaele, Henk, ‘Achilles or Adonis: Controversies Surrounding the Male Body as National Symbol in Georgian England’, Gender & History, 28, 1 (2016) 77-101

hooks, bell, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love (New York: Washington Square Books, 2004)

Leslie, Esther, ‘Those in Glass Houses Laugh’, Verso, 27 September 2016, accessed from <https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/2855-those-in-glass-houses-laugh> [accessed 16 March 2023]

Mosse, George L., The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996)

Sontag, Susan, ‘Fascinating Fascism’, in Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Vintage Books, 1981) 73-105