Writing about colonial statues, the biographies of their depicted subjects, and acts of contestation in the present can often feel like a gloomy affair. Of the numerous individuals recorded in the Cast in Stone database, we find types such as slave-owners, slave-traders, colonial administrators, race scientists, war criminals and the like. Many of these men – and they are almost always men – inflicted serious pain, trauma, and death on ordinary people through acts of physical and epistemic violence during their lives. In drawing attention to the enduring legacies of such violence and the historical erasure embodied by such memorials to these “great men”, acts of anti-racist protest against statues often take an equally serious and sober tone: words of indictment are scrawled on their plinths, placards listing their crimes are affixed to their bodies, and blood red graffiti is splashed all over them.

Popular protest against statues needn’t always be so sad and heavy however. In June 1979, for instance, black Zimbabweans celebrated their triumph over white-minority rule by placing a sign saying “THIS SPACE TO LET” in the hands of Cecil Rhodes’ statue in Salisbury. Churchill has had a green mohawk dutifully placed upon his bald head, and if you happen to be a certain well-known “Milk Snatcher” in Grantham, you can expect a welcome egg thrown in your face from time to time.

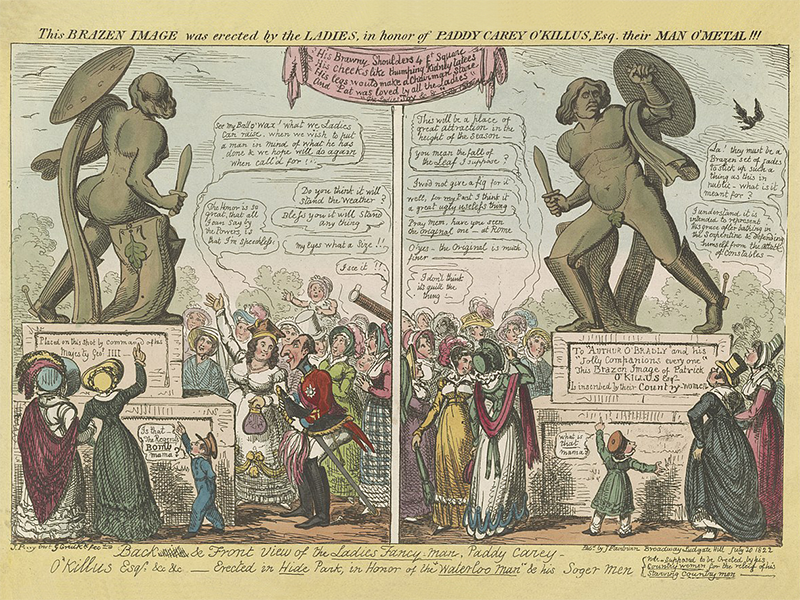

So, in the spirit of such interventions, this blog post looks at the power of laughter and comedy in destabilising the meaning of colonial statues. More specifically, it focuses on Richard Westmacott’s scantily-clad Wellington Monument in London as an early example of how an imperial statue, intended as a model symbol of civic masculinity, could be immediately subverted upon its unveiling through widespread public ridicule.