How to cite this page Comment citer cette page

Repatriated Colonial Statues: Monuments and Imperial Geography

Tommy Maddinson

Introduction

One of the key outcomes of this collective project has been the emphasis on the ability of colonial statues to move. While their creators may have intended for them to be fixed, immovable objects, statues were often anything but: they have frequently been put into storage and then taken out of storage, dismantled and then re-erected, toppled and then re-assembled. Statues have travelled distances great and small, moving across streets, cities, countries, and even continents.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the British Empire exported a number of statues from the metropole to its colonies. Once installed in the colonies, these statues became micro-sites of historical memory and ritual, serving a wide range of material and symbolic purposes across heterogenous and diverse imperial settings. For the rulers of the empire, statues were an instrument by which aesthetic production, fused together with wider processes of spatial production, could remake the physical and psychological landscape of the colonies. For empire’s dissidents, however, statues could just as equally be sites of political and aesthetic protest, functioning as symbolic battlefields in the wider conflicts over political representation and the (il)legitimacy of colonial rule. Indeed, in the turbulent wake of the Second World War, these memorials became increasingly contested by anticolonial movements across the planet, seeking out new forms of cultural freedom from European rule. Many were torn down or removed from public spaces and put into storage.

With the tide turning against colonial rule, government ministers and private individuals in metropolitan Britain were faced with a difficult decision in responding to the threats facing these statues. The first option, and the most economically viable one, was simply to do nothing and to accept that statues in the postcolonies could not be recovered. The second, rarer option was repatriation: salvaging the unwanted statues by having them shipped and returned to Britain.

This case study examines nine colonial statues that were repatriated to Britain after the end of empire. The names of the statues and their dates of repatriation are as follows: Henry Hardinge (1950); Horatio Kitchener (1958); Charles Gordon (1958); John Nicholson (1958); Alexander Taylor (1960); John Lawrence (1962); William Mackinnon (1964); Rufus Isaacs (1969); and "The Trooper" (1979/2008).

Background

While the individual biography of each statue is beyond the scope of this case study, we can make some general remarks about the background of this particular group of repatriated statues. With the exception of William Mackinnon (founder of the Imperial British East Africa Company), Rufus Isaacs (Viceroy and Governor-General of India in the 1920s), and Wayne Hannakom (a Rhodesian soldier), all of these statues depict military men who fought on behalf of the British Empire. The statues were also installed at different time points in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, starting with Hardinge (1858) and ending with The Trooper (1979). The majority of these statues were sent to India, although the statue of Kitchener is a notable exception in that it was first installed in Kolkata in 1912, but ended up being relocated to Sudan eight years later.

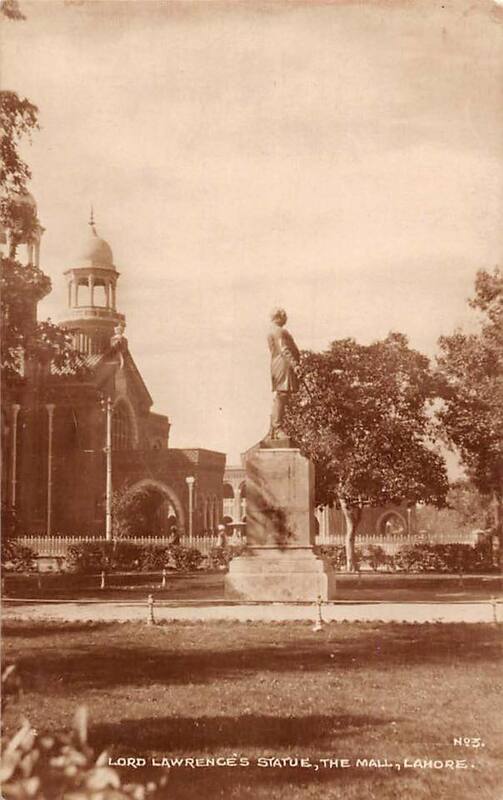

These statues' importance to colonial governmentalities, the remaking of public space, and anticolonial resistance to imperial iconography is perhaps best illustrated by Joseph Edgar Boehm's statue of John Lawrence. First installed outside of Lahore High Court in 1887 as part of the festivities for Queen Victoria's golden jubilee, the statue of Lawrence holding a pen and a sword, with a provocative inscription "By which will ye be governed, the pen or the sword?" underneath, became a fierce site of contestation in the city, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1921, for example, Lahore's Municipal Committee launched a campaign to try to remove the statue of Lawrence, or at least have its inscription effaced, which provoked a strong colonial response and police protection for the statue. With the statue unable to be removed through official channels, several of Lahore's citizens undertook their own acts of guerilla protest. In 1925, the statue of Lawrence had its pen stolen and sword defaced, and seven years later, in 1932, four Sikh men were arrested for having damaged the statue with hammers and chisels.

Repatriation

As the example of Lawrence illustrates, these statues were highly contested objects in colonial and postcolonial public space. In the absence of any meaningful self-determination, however, it was only with the achievement of national independence from British rule that colonial subjects could have a voice over representation in public spaces.

Save for backdoor private discussions, foreign officials in metropolitan Britain were now largely circumscribed in their ability to decide what would happen to statues in the former colonies. Hence, most efforts to repatriate these statues came from private individuals, such as family members, businessmen, or even old-schoolboy networks, as will soon become clearer. The only real notable case of visible governmental intervention in statue repatriation was the two statues of Kitchener and Gordon in Sudan, both of which were publicly discussed in Parliament and then brought back to the UK in 1958. The costs and logistics of repatriating statues must have been the biggest hurdle to any real concerted effort: the relocation of the Lawrence statue in 1962, for example, involved complex negotiations between the Commonwealth Relations Office, shipping companies, retired Indian Civil Service officials, and Pakistani authorities (including the President of Pakistan, Muhammad Ayub Khan, who gave final permission for its release).

Nevertheless, several colonial statues did make it back to Britain, and examining their final location(s) provides a unique lens into how their embodied historical memories could be rearticulated in Britain. Interestingly, the most common destination for repatriated statues ended up being educational establishments across the UK. These included Gordon's School, Woking (Gordon), The Royal School, Dungannon (Nicholson), Foyle College, Derry-Londonderry (Lawrence) and Keil School, Dumbarton (Mackinnon). The statue of Taylor was sent to the former site of the Royal Indian Engineering College in Surrey, where he had been President from 1880 to 1896, while Kitchener ended up near to the Royal School of Military Engineering in Chatham.

Private family estates were the next most common destination for these statues. The statue of Hardinge, one of the earliest to be repatriated after the end of empire, now stands in the grounds of Albion Villa. The Trooper took a more roundabout route. It was initally smuggled out of Zimbabwe to apartheid South Africa after the end of white minority rule in Rhodesia in 1979, but later moved to Britain at some stage in the late 1990s. It then entered the collections of the now-dissolved British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol in the early 2000s, before being erected in its current position at the Salisbury family's seat at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire in 2008. The statue of Isaacs is the only usual exception in that the Isaacs family had the memorial repatriated, but it was re-erected in a public park in Reading in 1971.

In the case of these family statues, the interest in having these statues returned to Britain seems fairly apparent. What is less clear, however, are the reasons for having these statues brought to educational establishments across the UK in the 1950s and 1960s. The most immediate justification was usually that the statue's historical subject had either been an ex-pupil or had some kind of association with the school or local area, but this seems a little too neat-and-tidy as an explanation given the challenges involved in statue repatriation. At the heart of the matter is this paradox: why go the lengths to bring these statues of imperial heroes back for future generations in Britain, when there was no longer any empire for them to go out to? Was this really in the interests of young people growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, or was this about an older generation trying to save face amidst the slow collapse of imperial rule?

Conclusion

Empire was about putting things in motion and, as we’ve seen with this case study, statues were no exception to that rule. The rhizomatic workings of colonial power across the planet make it impossible to tell the story of imperial statues in metropolitan Britain as a singular, rooted story, running in a straight line from the birth of statues to their eventual deaths. The history of repatriated statues instead suggests a much more complex historical genealogy, one in which statues can be connected to different points in time and space. It also reveals a much longer history behind the complex efforts to defend and resist the removal of colonial statues, something which will inevitably dominate one side of how our current "culture wars" are to be remembered, and points to their political endurance amidst the shifting currents of historical change.

Viewed from this angle, colonial statues seem to be zombie-like in their ability to defy death and to return to haunt us in the present. After all, statues, by definition, are depictions of human subjects beyond their actual physical life-span. Like many memories of empire, they continue to 'weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living' today.

Further readings

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (London: Penguin Classics, 2017)

Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1955)

Joan Coutu, Persuasion and Propaganda: Monuments and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2006)

Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76 (London: Penguin Classics, 2020)

Sophia Labadi, 'Colonial Statues in Post-colonial Africa: A Multidimensional Heritage', International Journal of Heritage Studies, 30, 3 (2024) 318-331 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2294738>

Tommy Maddinson, 'Repatriating Colonial Statues in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries', Cast in Stone, 19 January 2024, <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2024/01/19/repatriating-colonial-statues-in-the-twentieth-and-twenty-first-centuries/>

Paul M. McGarr, 'The Viceroys are Disappearing from the Roundabouts in Delhi: British symbols of power in post-colonial India', Modern Asian Studies, 49, 3 (2015) 787-831, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X14000080>

Mary Ann Steggles, Statues of the Raj (London: BACSA, 2000)

Mary Ann Steggles and Richard Barnes, British Sculpture in India: New Views and Old Memories (Norwich: Frontier Publishing, 2011)