I finally found time in January this year 2024 to take myself to Reading, to explore the Tweed archive, the collection of private papers, sketchbooks and artefacts deposited by the daughters of the sculptor John Tweed in Reading Museum in 1968. I received a wonderful welcome from the art curator and her team, as she gave up an entire day in order to accompany me to the museum store and literally walk me through the materials. This of course, is the reality of research in smaller, regional archives and museums, there is rarely dedicated staff available to facilitate research and access depends on the generosity of very busy staff with many other things to do. However, when one does secure the time of such colleagues, the depth of knowledge that they can offer about the area is a resource in its own right.

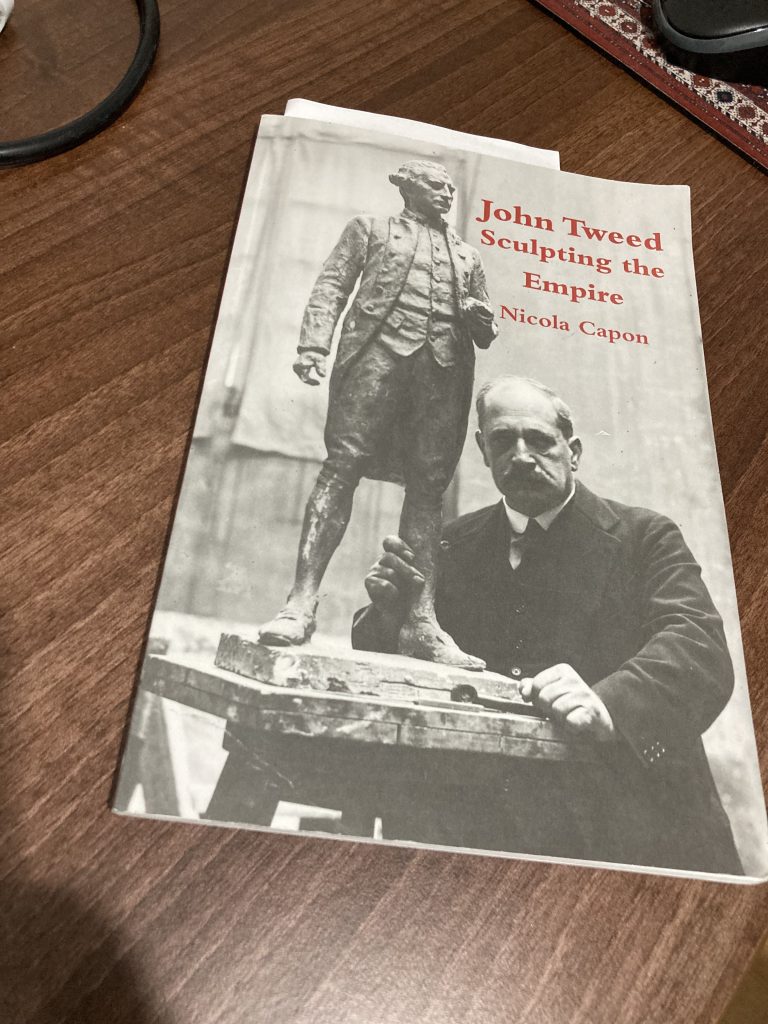

In our Cast in Stone database, which is actively in development, John Tweed stands out as the most prolific sculptor of colonial statues; within England, he is known to have sculpted twelve prominent statues of individuals who were colonial officials or British statesmen closely concerned with imperial or colonial matters. He may indeed be associated with further statues in Scotland and Wales, but we are not aware of this so far. Indeed, in a splendid thesis turned book, Nicola Capon called him the ’empire sculptor.’

Nicola Capon’s book was the result of a funded project to catalogue the Tweed archive, and to co-curate an exhibition, which ran in summer 2013. The resulting catalogue, detailed and systematic, was then incorporated into Reading Museum’s art catalogue, and consisted of roughly 860 items.

My interest in Tweed arose from my efforts to piece together the story of the statue of Robert Clive in Whitehall, London, erected in 1912. This statue was really the pet project of Lord George Nathaniel Curzon, resigned Viceroy of India, known to students of Indian history for his vicious hatred of Bengali nationalists, but also for being the moderniser of the Archaeological Survey of India. Prodded by a letter-writer to the Times in 1907 who lamented the lack of adequate public memorials for Clive, Lord Curzon set up a committee which gathered subscriptions, organised a competition and commissioned Tweed to create the statue. The process was much more complex than it sounds here; and in fact, I found out how much more complex when I looked through the Tweed archive yesterday and could feel Tweed clutching his head at the endless stream of instructions and admonitions emanating from Curzon.

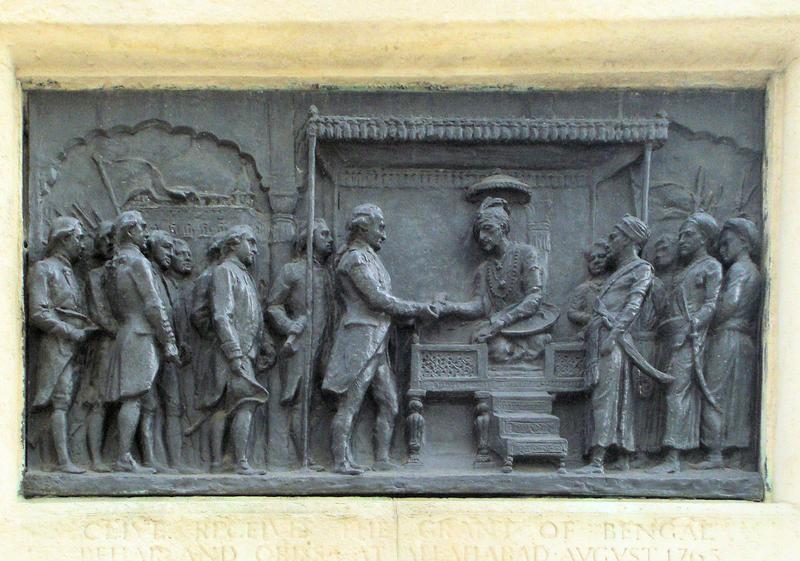

A great deal of the communication was, unexpectedly, about historical research. Tweed was eventually convinced to add relief panels to the plinth of the statue, three panels depicting three major historic events associated with Robert Clive’s career in India. There were the battles of Arcot and Plassey, which made the southern states of Arcot and Bengal client-regimes of the East India Company, respectively. There was also the securing of the fictive grant of the Diwani or tax-collection rights in Bengal from the defeated and supine Mughal emperor in 1765. Having never been to India, Tweed had no idea how these places, people and scenes ought to look. It turned out that the old India hands, including Clive, could find few historical records to provide that information from, too. In the end, Arcot’s fort was depicted by a pencil-sketch in a letter from Curzon, and Tweed was given access to Powis castle, the seat of the Clive dynasty in Wales, to view portraits of Clive. His bas-relief of the Diwani scene was based on a 1818 Benjamin West painting, to which he added information provided by friends about thrones in Tehran (which of course is not in India, but such peremptory conflations are totally usual with Orientalism, on which hear Edward Said, at 6: 53). Mimetic realism, then, depended on many layers of artistic and literary imagination as well as personal memories.

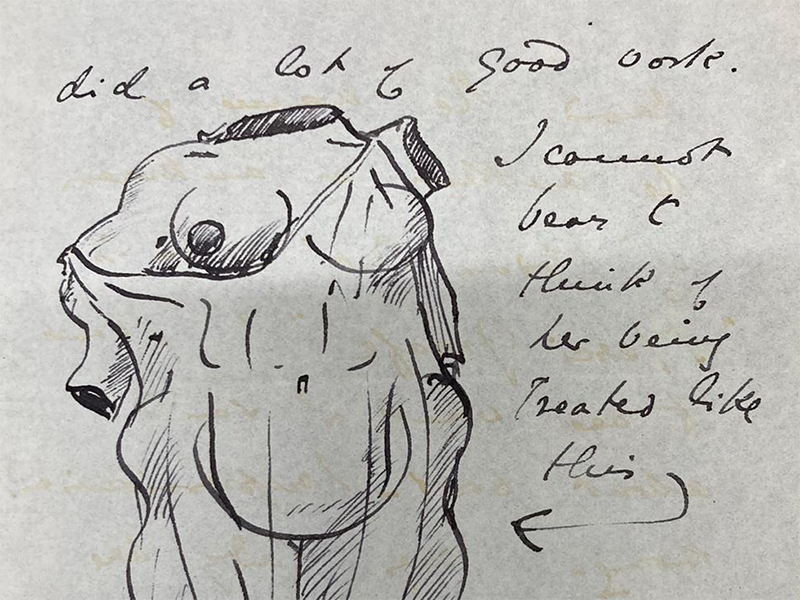

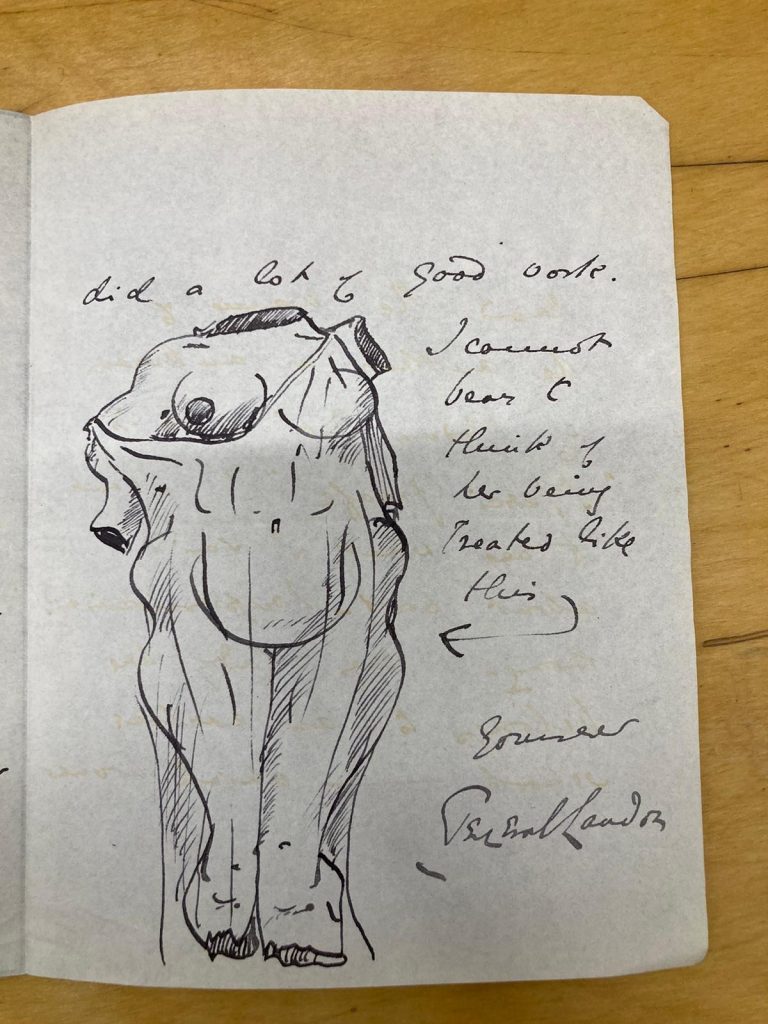

As in a personal collection, however, there are always surprising snippets where correspondents reveal their views in unexpected ways. So it was in a letter written to Tweed by Perceval Landon, traveller, writer and a constant friend and patron of John Tweed, also a member of the Clive statue committee. Commenting on a book on modern art written by an author whose name he purported to be unable to read, but attempted to spell as ‘Merci Graafe’, Landon said to his friend, “I want to see what us said about post-Impressionism but my lady here belongs to an earlier school – which […] did a lot of good work. I cannot bear to think of her being treated like this.” The curved arrow pointed to the image below.

Having overcome my initial horror as I thought that this was a rude sketch of a woman art historian in a wink-wink conversation between two men being lads, I was still amused when the art curator wisely pointed out that Langdon was probably expressing disapproval of modernist portraiture. I then wondered – what was horrific about this sketch to Landon – many, if not most women, do in fact look just like this, whatever their girth – lumpy and bumpy. Was Landon objecting to biological truth intruding into the hallowed arena of art?

And is this why the memorial statues are so wrong in so many ways? That they are idealised presentations of people, but we told that to look at them, warts and all, would be to disrespect them?