How to cite this page Comment citer cette page

Redvers Buller in Exeter

Nicola Thomas and Tommy Maddinson

'A Silent But Eloquent Answer': The Redvers Buller Statue Campaign, 1901-1905

To understand the origins of the statue of Redvers Buller and his horse in Exeter, we have to go back to a controversy that erupted in October 22nd, 1901 whilst Britain was at war with the Boer Republics in South Africa. When the Second Boer War broke out in 1899, General Sir Redvers Buller had a long military service running for just over forty years, fighting in several colonial conflicts across three separate continents, and seemed to be reaching the pinnacle of his career when he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South Africa. Yet two years later, and this would all come down in an ugly crash when Buller was dismissed on half pay from the Army on October 22nd, 1901. Buller's dismissal was the result of a long-running conflict within the Army over his performance during the Boer War, particularly in light of the disastrous events of 'Black Week' in December 1899, as well as a carefully orchestrated campaign by his replacement Lord Frederick Roberts, the War Secretary St John Brodrick, and Times journalist Leo Amery. Buller had tried to defend himself in a speech in London on October 10th, 1901, but his quotations from confidential military telegrams provided an opportunity for his enemies and he was dismissed twelve days later. Buller would never recover again.

Buller's dismissal was met with an angry but divided reaction in Devon. Albert Edward Dunn, the Mayor of Exeter at the time, led the charge in support for Buller by announcing a meeting would be held at the Guildhall to consider how they would respond. Other local politicians, however, were more cautious about wading into in the controversy: John Kennaway, MP for Honiton, and Lord Morley, the chairman of Devon County Council, both expressed their opposition to Dunn's announcement and refused to attend the proposed meeting. Nevertheless, the Guildhall meeting went ahead and on October 26th, 1901, the “Buller Memorial Committee” was born in Exeter. The Committee was made up of nine men: Dunn, Edwin Charles Perry, Thomas Linscott, J. A. Loram, T. Moulding, W. Wreford, E.J. Domville, C.J. Ross, and W. H. Steer. Dunn, Perry, and Linscott all variously served as Mayors of Exeter between 1900 and 1905. On November 1st, 1901 – just under two weeks after Buller's dismissal – the Committee opened a shilling fund for subscriptions towards a memorial to Redvers Buller, with suggestions including a statue in Exeter, a statue on Plymouth Hoe, or a convalescent home for soldiers at Crediton.

The Committee initially struggled to garner support for the planned memorial, receiving a lukewarm response in the press as well as criticism from several County Magnates. The turning point of the campaign came when Thomas Ashton, 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde, provided a 'substantial cheque' towards the memorial, and donations to the shilling fund started to increase thereafter. By March 1902, with £1,400 to £1,500 raised in subscriptions, the Committee had decided to settle on a statue of Buller in Exeter.

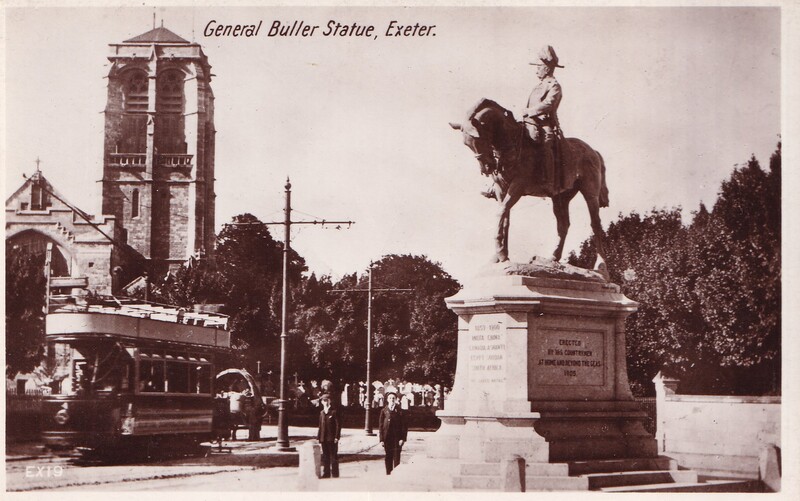

In May 1903, the Committee commissioned a design for an equestrian statue of Buller from the sculptor Captain Adrian Jones. As a former military veterinarian, Jones had himself served in several colonial conflicts in Ethiopia, Ireland, South Africa and Egypt from 1867 to 1890. After a visit to Devon in September 1903, where he also attended the Buller's Crediton Arts and Crafts Exhibition, Jones decided on the triangular space between the entrance to Hele's School (today Exeter College) and Bury Meadow as the best site for the statue. Further assistance towards the construction of the statue came from John St Aubyn, 1st Baron St. Levan, who donated the Cornish granite for the statue's plinth. St Aubyn was Buller's brother-in-law, and his son John Townshend St Aubyn had been Buller's Aide-de-camp during the 1884 Suakin Expedition in Sudan.

The Design and Location of the Memorial

Examining the statue's design and location reveals the intricate details of how the Committee wanted to craft Buller's historical memory. The statue must be viewed through the prism of the controversy over Buller's dismissal. The Buller Memorial Committee wanted his involvement in the Second Boer War to be remembered as a victory rather than a humiliating personal defeat. The memory of Buller's military and imperial triumphs was to be celebrated, and the controversy over his dismissal to be quietly forgotten.

The top inscription on the front of the plinth list the places where Buller fought during his four-decades long imperial career (India, China, Canada, Ashanti (Ghana), Egypt, Sudan and South Africa) while the inscription on the left hand side lists his military awards and titles, including the Victoria Cross, the CCB and the CCMC. Though not immediately apparent to the modern viewer, the lines "HE SAVED NATAL" and the bronze horse, "Biffen", are both references to Buller's (eventual) victory at the Siege of Ladysmith on February 28th 1900 during the Second Boer War. As a symbolic triumph for Buller during the conflict, the memory of Ladysmith was a crucial mythmaking device in the memorial campaign. Ladysmith operated as a kind of screen memory, or a counterweight, that could be counterposed to the devastating events of Black Week in December the previous year, when 2,700 men had died in a single week under Buller's command. Indeed, the statue campaign was accompanied by an annual "Ladysmith Day" held in Exeter from 1902 until at least 1905, usually attended by Buller and/or his wife Audrey Buller, which must have aided the subscription fund.

The final point worth noting is the location of the statue. Buller and his horse sit at a crucial point in Exeter's spatial environment. In its position on New North Road, the statue is situated along one of the main arteries leading in and out of the city centre. The front of the statue looks towards the general direction of Exeter Cathedral, while the reverse of the statue faces (to much local annoyance) towards Buller's home town of Crediton, and both the Cathedral and Crediton have their own memorials to Buller. This civic and perhaps religious positionality is complemented by the statue's location outside an educational establishment, something which a century later has been picked up on by council discussions around the statue. Buller's statue, although the product of a reputational controversy, was designed to instil a particular vision of "imperial manhood" for future male generations of empire. Given the horrendous death rates during the Second Boer War – over 20,000 Britons died in the conflict. – we can perhaps detect a latent desire here to reaffirm the ideal of militarised masculinity at a crisis juncture point.

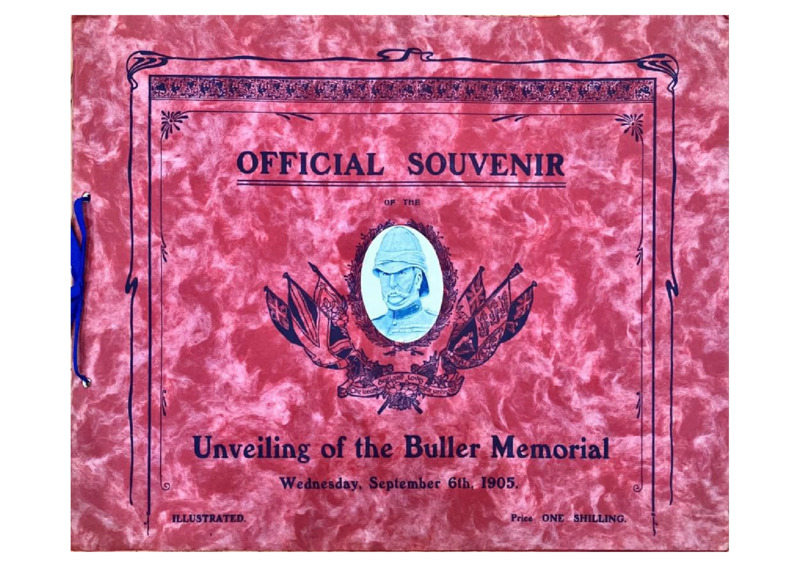

The Unveiling Ceremony, September 6th, 1905

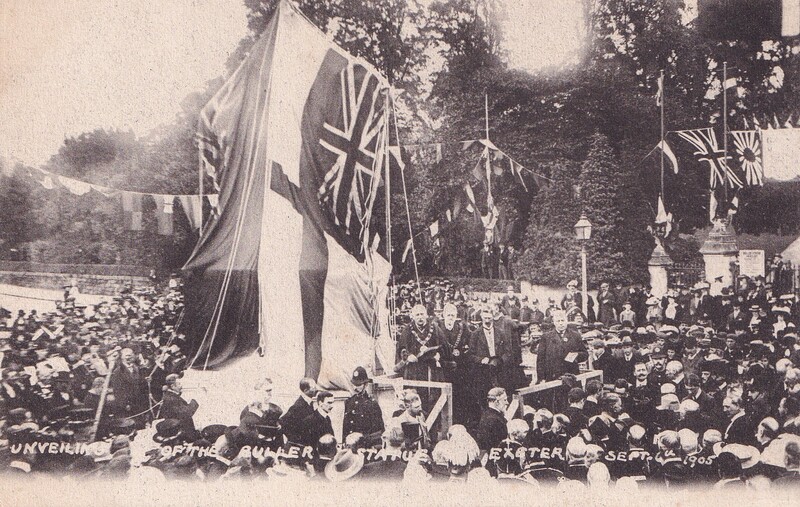

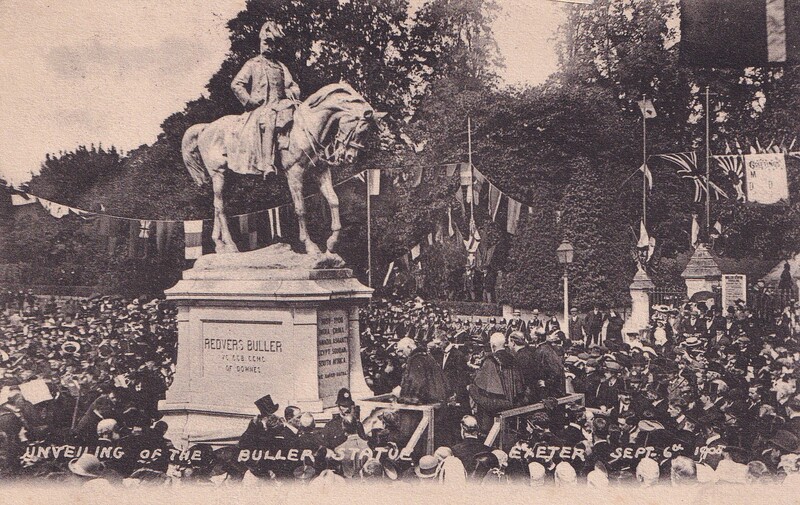

On September 6th, 1905, the equestrian statue of Buller was finally unveiled. While the Exeter Flying Post proclaimed the occasion as “Ladysmith all over again”, the actual events of the day did not quite go as the Memorial Committee were hoping. Garnet Wolseley, under whom Buller had served during several colonial conflicts, was due to speak at the unveiling ceremony, but ended up being unable to attend due to poor health. In his place stepped the Lord Lieutenant of Devon, Hugh Fortescue (whose brother, John William Fortescue, was a close friend of Buller and had helped him with testifying during the parliamentary inquiry into the war) to lead the proceedings. The main unveiling event was comprised of speeches from the Committee Chair Albert Dunn, Fortescue, and the Mayor of Exeter Thomas Linscott. An extract of Wolseley's speech, read by Fortescue, went as follows:

The main unveiling ceremony was followed by a luncheon at Victoria Hall and a veterans' tea at Bury Meadow. Buller himself did not attend the statue's unveiling, but he did attend the luncheon and tea events. The speeches and testimonials to Buller throughout the day, which can be read in the transcribed Exeter Flying Post document, reflect many of the points previously discussed throughout this piece: the fierce political controversy over Buller's dismissal, the celebration of Buller's career and his victory at Ladysmith, and the importance of his historical memory to future generations. The Mayor of Exeter, Thomas Linscott, perhaps best summed up the purpose of the statue when he argued:

Investigating the other attendees (and non-attendees) of the day's events also reveals some interesting colonial connections. Paul Methuen, one of Buller's fellow commanders during the war, was present, as was Frederick Stopford. Horatio Kitchener did not attend (he was stationed in India at the time) and nor did Lord Roberts for obvious reasons. Many local politicians from across Devon also attended the unveiling, some of whom had their own entanglements with empire. These included George William Kekewich, whose father, Samuel Trehawke Kekewich, had received compensation as a trustee for enslaved people in Grenada, Ernest Joseph Soares, the son of a Portuguese-Indian merchant from Liverpool, and Harry Trelawney Eve, the son of a Jamaican merchant.

Further readings

Ghee Bowman, 'Exeter's Fourth Plinth?', Cast in Stone, 3 April 2024, <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2024/04/03/exeters-fourth-plinth/>

Peter Donaldson, Remembering the South African War: Britain and the Memory of the Anglo-Boer War, from 1899 to the Present (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), <https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/31644>

Alan Lester, 'Redver Buller’s Empire', 22 August 2023, <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2023/08/22/redver-bullers-empire/>

Tommy Maddinson, ‘Colonial Statues, Public Space and Masculinity in Postcolonial Britain’, Cast in Stone, 12 December 2023, <https://castinstone.exeter.ac.uk/en/2023/12/12/colonial-statues-public-space-and-masculinity-in-postcolonial-britain/>

Neha Shaji, 'Decolonise Exeter', Exeposé, 11 June 2020, <https://exepose.com/2020/06/11/decolonise-exeter/>