How to cite this page Comment citer cette page

Robert Milligan: Hidden moments of contest

Georgie Wemyss

Political contestation is a key theme in the biographies of colonial statues. Funding, commissioning, placing, relocating, and maintaining monuments that represent colonial power are consequences of accumulated global and local political struggles. However, meaningful contests may not be visible to all. Depending on location and context, the opposition to statues may be ignored or derided by the statue’s admirers. The removal, mutilation, or destruction of such memorials, as Black Lives Matter actions show, expose generations of colonial violence, trauma and conflict.

This case study focuses on two key moments in the biography of the statue of Robert Milligan that did not make headlines but which capture traces of wider political contests that shaped that biography. It shows how the hidden contests that contextualise those moments in 1997 and 2007 contributed to its very public removal in 2020.

Milligan

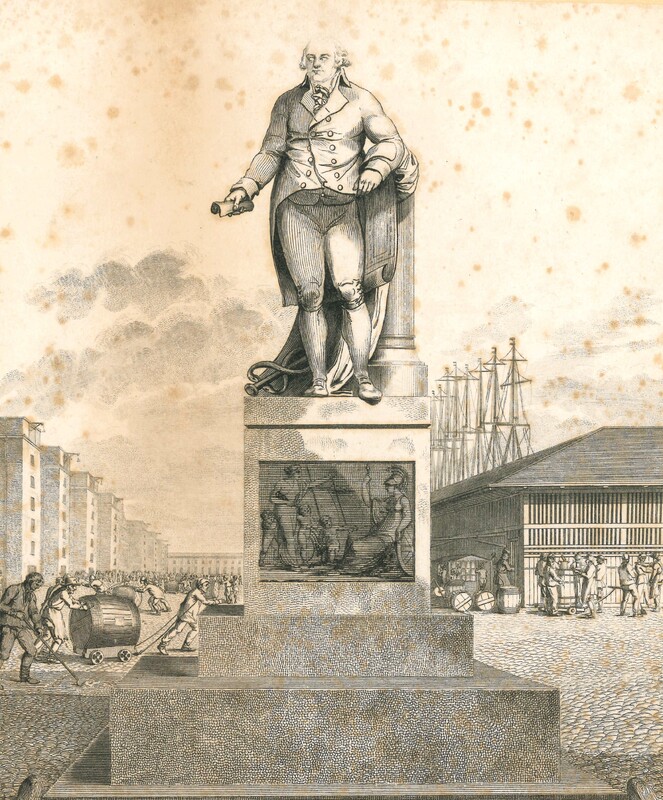

Robert Milligan (1746-1809) was a prominent slave trader and owner of two plantations in Jamaica with a population of 526 enslaved Africans. He campaigned forcefully against the abolition of the slave trade and was eulogised by co-directors of the West India Dock Company for his work in establishing the West India Docks, built to enhance the profitability of shipping between Caribbean colonies and London. His devotees commissioned the bronze statue, to be placed within the West India Docks, from the sculptor Richard Westmacott, whose other monuments to white colonists were instituted across the British Empire.

Changing locations

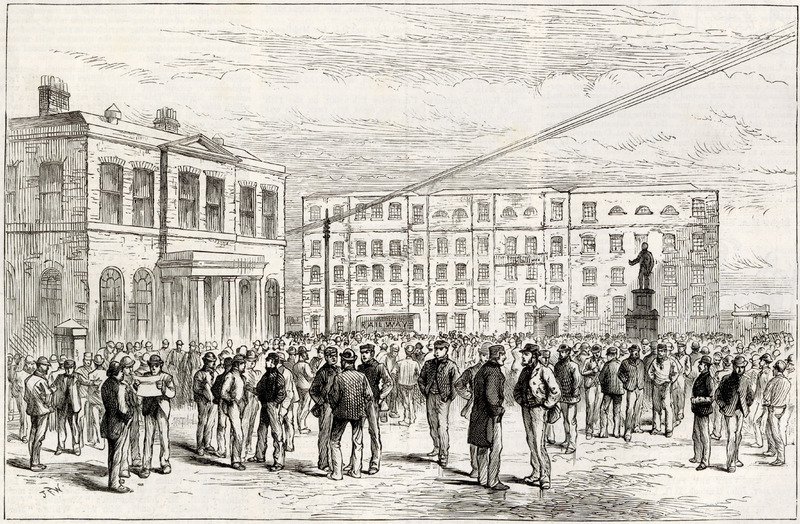

The statue was moved many times in the two centuries between its public inauguration and exit. Obstructing traffic rather than political contest was the most common reason for this. Its prominent 1813 location in front of the entrance to the Dock Offices and the Hibbert Gate entrance to the West India Docks blocked horse-drawn carts so that in 1875 it was moved high atop the central pier of the entrance gateway on West India Dock Road.

In 1943 that pier was removed to allow for wider vehicles and the statue was put into storage for three decades. In the 1970s it reappeared in a location upriver outside the offices of the Port of London Authority (PLA) but was returned to storage in the 1980s when the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) embarked on the regeneration of the redundant dock complexes. In 1997 the statue was returned to its original 1813 location in front of the, by now listed, Dock Offices, but to avoid traffic damage it was soon moved a few metres east to stand directly in front of the entrance of what would open as the Museum of London Docklands (MoLD). It remained there until 2020 when the Canal and River Trust (CRT), the Museum of London (MoL) and Tower Hamlets Council (THC) scrambled to move it back into storage the day after the toppling of the Colston statue in Bristol.

Changing institutional identities: ownership, regulation and obfuscation

The number of different organisations that had a stake in the statue, together with their changing institutional identities over time, contributed to the apparently uncontested 1997 placement and twenty-first century longevity of the statue. Responsibility for the statue was obscured for those who objected to it. This meant that its owners, those who made planning decisions and those who institutionalised the dominant narratives about West India Dock histories, were able to distance themselves from associations of guilt and from decision-making.

In 2020 the owner of the statue and the land that it stood on was a charity, the Canal & River Trust (CRT). It had taken over the assets, including the statue of Milligan, and responsibilities of the UK government body, from British Waterways (BW) in 2012. Since the 1960s BW had managed the UK’s docks, canals and rivers and the surrounding structures and buildings.

Between 1981 and 1998 the LDDC's planning powers over-rode those of the local Tower Hamlets Council. The LDDC had been set up in 1981 by the Conservative government as a devolved government agency that aimed to redevelop the area of high unemployment and derelict buildings following the closure of the docks. It was dissolved in 1998 by which time the West India Docks was being transformed with the glass and steel towers of the Canary Wharf financial district. The Museum in Docklands Project (MiD-P) was a collecting and storage programme initiated by the MoL in 1979 to record the deindustrialisation of the area. The MiD-P worked closely with the LDDC and PLA to acquire the museum site and alongside produced travelling exhibitions and education resources about history of the dock area. From 1994 the MiD-P was controlled by a new independent trust (The Museum of the Port of London and Docklands Trust). In 2003, renamed the Museum of London Docklands, it opened in the sugar warehouse - partially funded by the LDDC and under the control of the Museum of London. (Aylett, 2022, Chapter 8, Paywall).

1997: Moment of reinstatement

A small picture in the 1997 LDDC Annual Report shows the Joint CEO of the LDDC and the Director of the Museum of London (MoL) shaking hands in front of the statue as they 'welcomed the return' to its 1813 site. The image of three powerful white men represents the strength of a celebratory narrative about the statue and the docks that obscured viewpoints that contested its re-appearance.

The LDDC, the MiD-P, the MoL, the MoLD, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) and Tower Hamlets Council (THC) had all contributed to normalising the return of Milligan's avatar. The LDDC was a significant funder of the MoLD, having given the warehouse site and a capital grant of £3.5 million. The MiD-P had published a glossy marketing brochure, supported by the HLF, titled 'A New Museum for a New Millenium'. Its front cover reproduced an 1813 engraving of the Milligan statue in front of the Dock Offices. With no mention of empire or enslavement, the brochure spoke of the Grade 1 listed 'late Georgian warehouse', of exhibitions that 'will inform and entertain' and of the 'unique and historic ambience' that the museum would offer to Canary Wharf- based corporations in the 'Heritage Partnerships' scheme. A different marketing brochure produced at a similar time by Olympia and York Group, the developers of Canary Wharf, included the statue in its 1813 location in an architectural illustration of the development. In 1995, THC had rubber stamped permission given by the LDDC, for the erection of 'a statue on a stone plinth and pedestal' – no objections were raised, and the minutes did not record the identity of the statue.

There was also local support for Milligan's memorialisation. In December 1998 The Islander, a community newspaper, led with the headline 'The father of the Island revealed' alongside a photograph of the statue's head and another of the 1997 'welcome back' image. The article argued that Milligan was the genius who had persuaded powerful City merchants that the West India Docks should be built on the Isle of Dogs, rather than nearer the City of London.

Whilst the celebratory story of Milligan that denied histories of enslavement dominated, the reinstatement of the statue was contested by local people. Their voices were not heard because they were not consulted and once they found out about it, the political and economic context of that time meant many were challenging racism in more grassroots movements. During the recession of the early 1990s, as the LDDC gentrified the old docks, promises of jobs and housing for working class residents did not materialise. The borough experienced intense political conflict and racism before and after the election of a British National Party (BNP) councillor in 1993 whose manifesto demanded 'rights for whites' in social housing allocations, employment and welfare services.

Harry Cumberbatch MBE, a descendant of enslaved Africans who had lived on plantations in Barbados, was not aware of the statue until after the Museum of London Docklands opened in 2003. At that time, he was co-ordinator of the Tower Hamlets African and Caribbean Mental Health Organisation (THACMHO) working on their Health through History project. He said that he 'couldn't avoid seeing the statue of Robert Milligan as it lauded the front entrance of the building'. He expressed that for THACMHO members involved in researching eighteenth century African writers with local connections 'seeing the statue in their face was very disturbing' adding that 'such a prominent slave owner of African people was so publicly displayed and they were powerless to do anything about it'.

Leutha, a local resident also involved with THACMHO, found out about the statue after reading the 1998 The Islander article. He wrote to the editor of the The Islander that he found it offensive that they had failed to say that West India merchants were slave owners. Leutha also noted how the positioning of the statue in front of the Dock Office and warehouse gave 'a particular signification in that it became a representation of power'. Whilst both Leutha and Harry objected to the statue, they chose, in Leutha's words, to not 'dwell on Milligan' but to engage positively in activities aimed at improving existing lives.

2007: Moment of shrouding

In November 2007, guests to the opening ceremony of the London, Sugar & Slavery gallery at the MoLD had to navigate their route past the statue of Milligan on its pedestal. For this launch day only, the statue was concealed beneath a black shroud, bound with thick, black rope and floodlit. (Wemyss, 2016, p. 44)

Even before its 2003 opening, the MiD-P and MoL had been criticised for nostalgic representations of empire and the docks. Criticisms came from professionals within the changing museum sector as well as from visitors and community representatives. Change also came as government funders required museums to attract more diverse audiences and to improve commercial performance.

The museum responded to intellectual critique and market forces with the new London Sugar & Slavery gallery that aimed to highlight relationships between London's commercial wealth and colonial slave-ownership. It was partially funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund as part of the national commemorations for the bicentenary of the 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Because of their previous work, Harry Cumberbatch and Leutha were invited to be members of a consultative committee alongside scholars of enslavement and cultural activists. Harry told of the discomfort felt by committee members when 'the statue was outside while we were inside, looking at the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade'. The statue stayed in place because the museum did not own the statue or the land and there was not the political will to move it.

The black shroud and ropes demonstrated the committee's opposition to the statue and everything it represented. Harry photographed the image because he 'knew it was an important moment'. The image ensured that the message of resistance was not lost after the shroud was removed. At the same time, he celebrated the positive presence of the late chief, Adeyela Adelekan from the Orisha tradition who blessed the opening.

(Aylett, 2022 Paywall; Gleeson, 2023)

Over the twenty-three years since 1997, the painstaking and traumatic work of exposing histories of enslavement and empire, whilst making sure to amplify voices silenced by those histories, challenged the powerful narratives that normalised the celebration of Robert Milligan. For example, in 2018 the MoLD and some of the original Advisory Group members including Harry Cumberbatch and historian Professor Hakim Adi, held an event reflecting on ten years of the London, Sugar & Slavery gallery. Participants included artists, museum practitioners and researchers including the Young Historians Project, a collective of young people that challenges the underrepresentation of African and Caribbean historians at British universities. Historians Melissa Bennett and Kristy Warren, who had organised the event on behalf of MoLD, recorded that audience responses had ‘called for changes and updates to reflect new thinking and research, greater publicity in London and beyond, and more collaboration with schools, community groups and other black history and heritage organisations’ and some were 'critical about the gallery's overall narrative and its perceived lack of impact beyond the 2007 commemorations'. (Bennett and Warren, 2019).

In 2019, the MoL produced a short film that critiqued monuments such as Milligan's. Although hidden from public view, the critical work of community workers, academics, teachers and cultural activists all contributed to the movement that led to demonstrations, a public petition, the re-shrouding and towing away of the statue on the 9th June 2020.

Post Script

The Statue

Following the removal of the statue, the museum produced a teaching resource titled 'Why was the statue of Robert Milligan removed?'. As well as explaining the context of its removal and encouraging critical discussion of monuments, it included that THC, CRT and the MoLD had 'formed a consortium to discuss the future of this statue' and that they were 'working with the local community to inform this future'. In March 2022 the three institutions announced that, following public consultation, the statue was joining the collection of the MoLD where it would remain in storage awaiting further consultation about how it should be displayed.

The Pyramid

In November 2020 a guerilla installation 'The Unknown Women' pyramid was erected on top of the plinth where the Milligan statue had stood. It remained without any official permission for 11 months. The artist, Kwame Djemjem described the pyramid as having 'a goddess on each side and they represent different races. My intention was to help heal the traumas of patriarchal oppression for the oppressed and the benevolent oppressors who want to reconcile'. The single bronze relief that had remained on the plinth after the statue was removed was accidentally enhanced by black and gold paint that had dripped from the artist's sign above. Djemjem stated that 'the bronze emblem honours imperialism and it now has black and gold paint over it. Oil and gold are the main driving force behind of imperialism. The synchronism is on point'.

Memorial

In 2026 a new memorial to honour the victims of the transatlantic slave trade and recognise London's role in the trade will be unveiled at the site of the Milligan statue. The plan has been developed by the Mayor of London's Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm which has worked with communities to develop the brief for the memorial. Six shortlisted artists will be announced in June 2024.

Further reading

Samuel Aylett, Legacies of an Imperial City: The Museum of London, 1976-2007 (London: Routledge, 2022)

Key source

Museums in Docklands, A New Museum for a New Millenium (n.d.)

These interviews have offered valuable knowledge and understanding for this essay:

Interview of Leutha, by Georgie Wemyss

Interview of Harry Cumberbatch MBE, by Georgie Wemyss

The author wishes to express her warm thanks to Sanjida Alam from Tower Hamlets Archives, for her help in locating images.