How to cite this page Comment citer cette page

Robert Clive in Shrewsbury and London: Making and Breaking Memories of Empire

Nandini Chatterjee

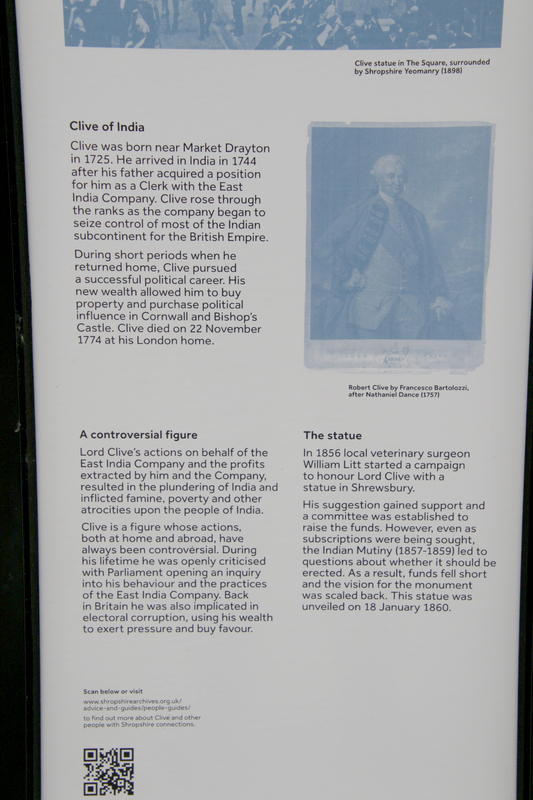

There are two Grade II listed outdoor statues of the colonial adventurer Robert Clive in the UK. The first, in Shrewsbury, was unveiled in 1860 and the other, in front of the current Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall, London, was unveiled in 1912 and moved to its current site in 1916. Both statues were responses anti-imperial movements in India, and were artefacts designed to regulate public memory, or as the historian Durba Ghosh has said, to 'stabilize history through monuments.' The statue in Shrewsbury was an immediate response to the Indian Mutiny of 1857, more correctly described as the mutiny of British East India Company soldiers and associated civil rebellion. The statue in London was a grander, and multi-sited project, led by Lord George Nathaniel Curzon, sometime Viceroy of India, famed for his dislike of Indian nationalists.

The making of the man

In many senses, Robert Clive was not an obvious candidate for public memorialisation. A poor and troublesome boy from the town of Market Drayton, in Shropshire (then called Salop), Robert Clive was sent to Madras (now Chennai), India in 1744 as a lowly clerk for the British East India Company. The wars and intrigues associated with the Company's transformation into a kingmaker and then a political power in India, gave Clive opportunities to make his mark. He engineered and participated in two major sets of battles and regime changes in India, first in the southern state of Arcot and then, more momentously, the wealthy province of Bengal. Intriguing with Mir Jafar, a relative and military commander of the Nawab or ruler of Bengal, Siraj ud-daula, Clive ensured that the military confrontation between the Company and the Nawab at Plassey in June 1757 was a foregone conclusion; Siraj and his son were killed, and Mir Jafar was appointed ruler of Bengal, with huge bounties from the state treasury as well as public loans, paid to the Company as well as Clive himself. The Battle of Plassey was to become important event in the constructed public memory of Clive in the following century.

After occupying the newly created position of Governor of Bengal for a few years, Clive returned home 1760, now among the wealthiest in Britain. Meanwhile, Bengal remained volatile as its rulers struggled with the Company to recover some autonomy. More wars ensued, drawing more Indian rulers and areas into conflict with the Company, eventually seeing the Mughal emperor defeated. Again sent to India, Clive used this opportunity to extract Mughal legitimacy for the corporate empire of the British East India Company by compelling the still-revered Mughal emperor to bestow the Grant of Diwani on the Company, putting the latter in charge of the taxes of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The British East India Company's extraction and complete misgovernment caused a devastating famine in Bengal in 1769-70, which may have wiped out a third of the population of the province.

Returning to England for the last time in 1767, Clive proceeded to buy properties around the country and to acquire the aristocratic title of Baron Plassey. His actions in India were the subject of a Parliamentary inquiry in May 1773, in which he staunchly defended himself. He died under still-mysterious circumstances in his own house in Berkeley Square, possibly due to an overdose of opium, which he took to relieve physical and psychological distress.

The making of the image

It is striking how the physical memory of Clive, represented in paintings, prints, and statues, was the result of intense collaboration - between the artist, historians, statesmen and Clive's family. Robert Clive was active in creating his own image during his lifetime. After acquiring his title, and a pocket borough to be elected Member of Parliament, Clive set about acquiring all the trappings of a British aristocrat. A striking portrait of Robert Clive was completed in or around 1762 by Thomas Gainsborough, known generally as a painter of pleasant English country scenes and portraits of British aristocrats. In Gainsborough’s portrait, Clive appears in in military uniform, holding some kind of a document – possibly a title. This painting, which remained in the possession of his descendants at Powis castle, was swiftly reproduced as a mezzotint print by James MacArdell and that print itself became the source of other prints. In 1766, John van Nost produced commemmorative medal depicting Clive's bust on one side and an allegorical image of Victory on the other, pointing to a monument saying 'NABOBS CAMP DESTROYED . . .VICTORIOUS AT PLASSEY . . .PEACE IN BENGAL.' An image of Clive had been put in circulation.

In between his Indian sojourns and Parliamentary enquiries, Clive also undertook the ‘Grand Tour’, which was the mandatory European sojourn for British aristocrats. During his tours in Italy, he purchased large numbers of valuable Renaissance paintings, and also formed the acquaintance of the American painter Benjamin West, known for his dramatic paintings of historical scenes. West would then be commissioned to produce a large oil-painting of the granting of the rights of Diwani, or revenue collection, by the Mughal emperor to the British East India Company, represented by Clive himself. This painting remained in Oakly Park, another of Clive’s properties, and became a crucial source for the design of the Clive statue in London.

The British East India Company also invested in refurbishing Clive's image. In 1760, the Company commissioned Peter Scheemakers, the Flemish sculptor credited with introducing neo-classical sculpture to Britain, to create a highly allegorical marble statue of Clive, depicting Clive as an orator-cum-soldier, with a Medusa shield warning off his detractors. The statue is currently housed in the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, London.

History-makers

Empire-building and image-making continued in the next generation. Robert Clive's son, Edward Clive , married into an old aristocratic family, and acquired the title of Earl of Powis, together with the castle at Powis, just across the border from Shropshire. Powis became the dynasty's seat, and an extraordinary intergenerational repository for Indian artefacts purchased and looted over two imperial careers. It was also where several important portraits of Robert Clive by major artists were held, together with the family's papers.

These family papers were made available to John Malcolm, himself a senior British East India Company official, a military commander and an enthusiastic Orientalist. Malcolm's The Life of Robert, Lord Clive, completed posthumously by yet another East India Company official, and published in 1836, depicted Robert Clive as a decisive empire builder, who seized the tide of history at momenst such as the Battle of Plassey. In this way and others, Powis castle and Clive's descendants would remain constant agents in the development of Clive's story over the next century.

It was 1857 that truly brought Clive back to life. In that year, the Indian soldiers of the massive British East India Company army, the largest standing army in the world at that point, mutinied against their officers and attempted to restore the Mughal emperor as the ruler of India. As the soldiers marched across the plains of northern India, they set off waves of civil rebellion; several major cities, including Delhi, fell out of British control. The rebellion caused horror in Britain as people struggled to understand why Indians did not wish to be ruled by the British. On 23 June 1857, in a deliberate reference to the 100-year anniversary of the Battle of Plassey, several British colonial officials and aristocrats met in London, declaring the need to commemorate Clive’s contribution to the nation. He was now declared a model of national virtue, whose public memorial could 'excite the moral principles of the rising generation.' One speaker proposed that the rebellion had been caused by the decline of virtues such as Clive’s among current British officials in India. A memorial committee was formed to raise funds; it received a starting contribution of £500 from the East India Company. The committee engaged an Italian sculptor trained in France, Carlo Marochetti, to create the statue. Marochetti had already produced two statues of Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, and several other statues of contemporary men associated with what were seen as heroic military endeavours. Marochetti’s statue, unveiled in 1860 in the market town of Shrewsbury, close to where Clive was born, showed Robert Clive as a middle-aged man with a belly, in military uniform, one hand on his hips, the other holding his hat, looking to the distance with a grim and determined expression, very much the military commander and empire builder.

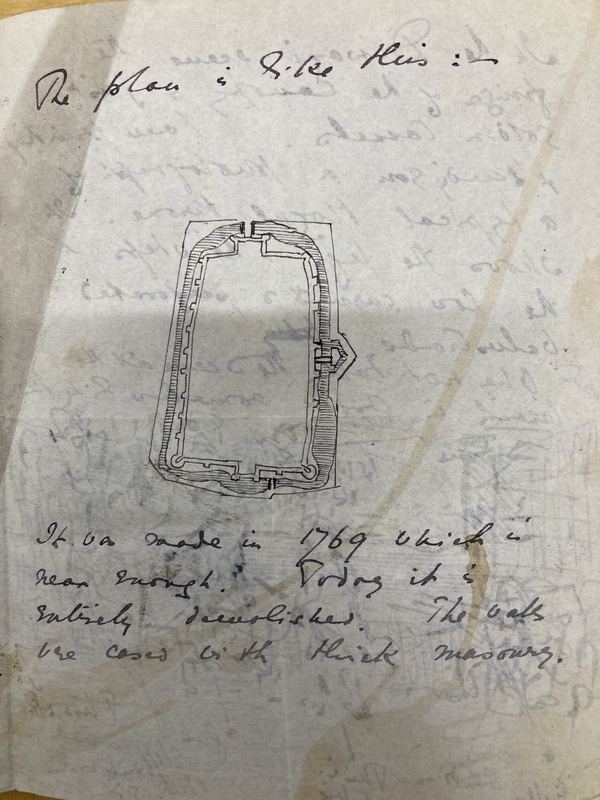

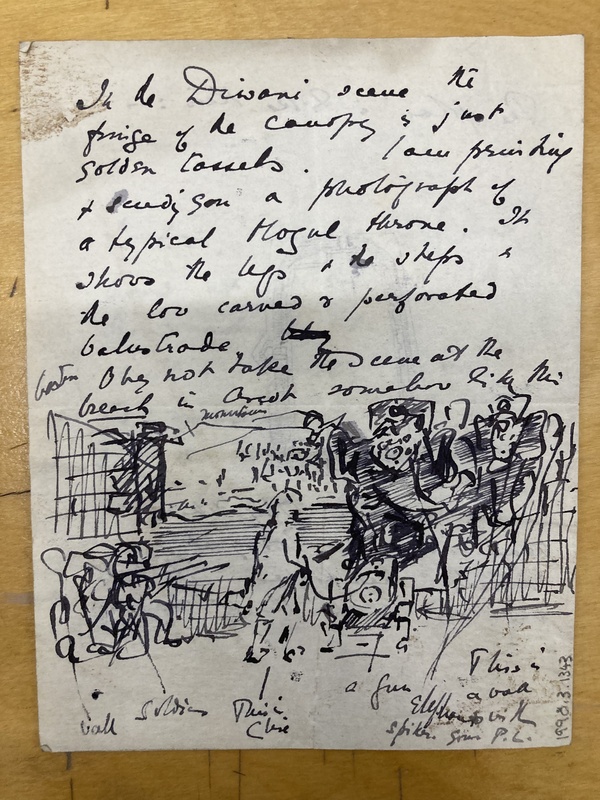

By the turn of the century, however, with Indian nationalists becoming increasingly vocal, and the first partition of Bengal raising considerable opposition from Hindu Bengali nationalists, some aristocrats in Britain felt that Clive's memory needed further projection. In March 1907, an Irish peer wrote to The Times complaining of the lack of any adequate memorial to Clive in Britain or in India. Within two days, Lord Curzon, recently resigned from the Viceroy of India's position, wrote back, reminding the original letter-writer of the statue in Shrewsbury, and his own efforts to establish a memorial in the battlefield in Plassey. But Curzon agreed that there needed to be more visible memorials, and proceeded to chair a Clive Memorial Committee, which raised enough funds within a year to commission two statues, one for London, and another for Calcutta. John Tweed, already known for his work on statues of Cecil Rhodes and other imperial figures, was commissioned for the task and instructed to be historically accurate in his depiction. Tweed's statue depicted a slimmer Clive, with a curved Indian sword or talwar in one hand and sheaf of papers in the other, loudly announcing the martial as well as legal rationale for British rule in India. Tweed was also convinced to add bronze bas-relief panels to the plinth, showing key events in Clive's career in India. Tweed had to be helped in depicting these places and events, which he had never seen. While the Benjamin West painting of the Grant of Diwani formed the basis of one panel; for Arcot he had to rely on a rather messy sketch prepared by his friend Perceval Landon.

Landon, at least, was gushing in his praise of the results. Possibly referring to a copy meant for transport to Calcutta, he said:

Memories in conflict

From the 1990s, an alternative memory about the events in Bengal between the 1750s and 1780s began to surface Britain. Some people remembered different events, or remembered the same events differently when it came to Clive in Bengal. These were the memories of the British Bangladeshi community, who were numerically concentrated in east London, in the areas such as Poplar and Spitalfields. South Asian sailors – referred to as lascars - had been present in Britain from the early eighteenth century. Many of them Muslim Bengalis, lascars (or lashkars) were part of a racialised, economically marginalised and necessarily mobile community, rendered invisible by the discriminatory employment policies of shipping companies, racist laws and social prejudice. In the inter-war period, some of them asserted their rights through unionisation, often led by Indian students and journalists.

From the 1950s, greater numbers of Bengali (mainly Sylheti) men arrived in Britain; many settled in East London, in the Tower Hamlets area. Clustering offered practical as well as psychological support; as the British-Bangladeshi community and heritage activist Muhammad Ahmedullah, who grew up in East London in the 1970s, remembered, 'We used to go to Tower Hamlets, Aldgate East area, just to ... see Bangladeshi people. (interview, at 49:00)' From the 1970s, more women were able to join their families; many such women worked from home as seamstresses, being the precursor of women garment industry workers of Bangladesh.

Children growing up in the 1980s in East London were subjected to vicious racist attacks on a regular basis. As Muhammad Ahmedullah remembered, the racism was so bad that teachers used to let the Bengali children go home earlier from school, so that they would not be attacked by gangs of white boys. The problem was serious enough for the Home Office to take evidence and explore solutions in a special Race Relations and Immigration Sub-Committee in 1986.

It was in this context of marginalisation and victimisation that the Bangladeshi community began to organise itself politically and culturally, claiming public space in Britain, their chosen homeland. Since the Labour Party would not put forward a Bangladeshi candidate, Muhammad Nurul Haque, a community organiser and housing activist resident in Tower Hamlets since 1970s, contested elections as an independent candidate, supported by the People's Alliance of East London, and in 1982, became the first Bangladeshi councillor in Britain. In 1982, the Kobi Nazrul Centre was established as a flagship arts and culture venue. In 1994, Bangladeshi-British businessman and community heritage activist Iqbal Wahhab organised the Festival of Bangladesh in London, and this provided occasion for the performance of a play about Siraj ud -daula, the unfortunate king of Bengal displaced by Robert Clive.

On 23 June 1997, Muhammad Nurul Haque organised a conference on the 240th anniversary of the Battle of Plassey at the Kobi Nazrul Centre. This became a bigger event next year. Muhammad Ahmedullah remembers it being attended by at least a hundred people and an emotional audience member 'shouting' that the statue of Clive should be taken down, and most of the audience supporting him. While Muhammad Ahmedullah did not remember Nurul Haque's rationale for organising the Plassey conferences, he guessed:

Eventually, Muhammad Ahmedullah himself became a significant community heritage activist. He founded the Brick Lane Circle in 2006, and organised a series of popular seminars and talks on the history of Bengal. This included a conference and cultural event on 23 June 2007, on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Plassey; and a second one on 23 June 2010.

A memory managed?

Since the 1950s, things had also been afoot in Shrewsbury. In 1956, the statue of Clive was recorded as a Grade II listed building, through the efforts of a J.T. Smith, who submitted a Ph.D. thesis in 1953 on the subject of Shrewsbury's architecture to the University of Birmingham. The town of Shrewsbury saw tremendous rebuilding in 1963 and severe flooding in 1964; the statue of Clive continued to stand through it.

The Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, which was established in 1835, and has since then been renamed and relocated several times, undertook an assessment of collections that were acquired from Africa and Asia, usually deposited by individuals with careers in those parts, often in connection with empire. Called 'ethnographic collections' according to standard museum parlance, most of these materials were moved to the Birmingham Museum, leaving the Shrewsbury Museum to focus on items of local relevance. However, a rump of those collections remained, and museum staff Emma-Kate Lanyon noted that in the years leading up to 2020 there was an effort to re-evaluate and re-contextualise these collections with expert advice. This process also alerted staff to the statue of Robert Clive, located practically on the doorstep. The museum also held items donated to the city by Clive himself. Thus, when competing petitions were submitted to the Shropshire Council in 2020, one demanding the removal of the statue and another demanding its retention, the museum decide to be pro-active, and againwon a grant from the West Midlands Museum Development programme for undertaking reinterpretation work.

As Emma-Kate Lanyon said (interview, at 20: 21):

Faced with competing petitions and demonstrations for and against the removal of the statue, Shropshire Council debated the topic on 20 July 2020 and decided that Clive was indeed a mercenary, the listed statue could not be easily removed. Instead, it noted that the Museum had been requested to provide better interpretation. Alexander Holmes-Brown, founder of the Shropshire Ethnic Minority Alliance (now renamed Shropshire Equality Means Action) remembering being told by his associates about the competing petitions, and drafting a question to the Council at short notice. He found the process frustrating and undemocratic, and the decision unacceptable. He was therefore happy when Martha Mondon from the Museum reached out the SEMA, and felt that it was a complete '180'.

The process of working with the museum was much more rewarding. Alexander Holmes-Brown remembered receiving a draft text and being invited to comment on it. While the result was not perhaps fully satisfactory, he was positive about the interaction, and commented:

"We were quite happy with the people from the museum service. They seem to have more interest in telling the truth than .. the Council. So OK, then museum's part of the Council. That the museum staff themselves have have a mind of their own." (interview, at 50: 47)

As for the text of the plaque, he said that it was:

"perhaps not as strong statement on the plaque as I would have wanted. I thought if people are going to be proud of this, let them say what they're proud of. Let the statue itself declare what it represents, and then we really have a testimony, perhaps even more to to what empire means, what colonialism means, and what it means to have monuments like this erected in celebration of of these achievements, and I think." But he also noted "I think we've done what we could with what we had and also I'm glad for having a testimony of Shropshire's real links to that global empire" (interview, at 1 hour 12)

One day, he hoped, the statue would be sent to the corner of a museum somewhere.

Technicolour Clive, or, stripping statues of power

Back in London, Clive continue to loom outside St. James's Park, London, providing a strange welcome to visitors to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Placed between the Imperial War Museum's Churchill War Rooms and a memorial to British victims of a bombing in Indonesia in 2002, the Clive statue forms the unfortunate apex of a jingoistic trangle.

On the other hand, in April 2024, in the Serpentine Gallery of Hyde Park, as part of an exhibition titled 'Suspended States', the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare CBE displayed his statue series Decolonising Structures, in which Clive formed part of a motley crew of colonial figures, all rendered somewhat hilarious in technicolour fibreglass. By reducing these London statues in size, and lowering their plinths, Shonibare explicitly aimed to reduce their grandour and power, but he also claimed that by dressing them in his signature 'African print' (which is in fact, Indonesian textile pattern commercialised by Dutch colonialists and marketed in Africa) and gold leaf, he is making them more beautiful. Shonibare is not for breaking statues, but he does think that they should be placed in museums, 'so people can understand the history of these people and what they did.' Murad Qureshi, Bangladeshi-British politician who has been vocal about the need to remove the Clive statue, is of the same opinion (Interview): he recommends replacing Clive's statue with one of a hero more suitable for the present times . He considered as alternatives the British computer scientist Alan Turing as well as the Bengali poet and educationist Rabindranath Tagore. The old Clive statue, he suggested, could join a line of other such statues of colonial figures, including that of Charles Napier, in Museum of London's new site at Smithfield Market.

The answer, then, might just lie in laughter, as one of our colleagues suggested, or it may lie in repurposing. Glaswegians, who have created an urban tradition of stating their political views through traffic cones placed on the head of the statue of Duke of Wellington, may indeed have found the answer.

Further readings

Richard Goebelt, "The memory of Lord Clive in Britain and beyond: Imperial hero and villain, " in Dominik Geppert and Frank Lorenz Muller eds. Sites of Imperial Memory: Commemorating colonial rule in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), pp. 136-152

These interviews have provided valuable information for this essay:

Interview of Muhammad Ahmedullah, by Nandini Chatterjee

Interview of Emma-Kate Lanyon, by Nandini Chatterjee

Interview of Alexander Holmes-Brown, by Nandini Chatterjee

Interview of Murad Qureshi, by Nandini Chatterjee

Many thanks to [Ms] Penelope Ward [former HER Officer Shropshire] for sharing her knowledge and research expertise; and to Dr Shailendra Bhandare, Ashmolean Museum, for sharing his expertise on commemmorative medals and coins.